The sun filters in through the forest and I wake up to my bird friends and cool air. I’m still tired, but know it’s best to move when it’s still crisp and the sun hasn’t quite hit me full on.

My routine is always to let out the air in my mattress, roll up my sleeping bag, dress, pack each bag,then send them out the door. No one visited last night, but I still start singing a made up song, “Bears of the forest!” to let them know by my wobbly soprano, to stay in the forest and not come too close.

I’ve impressed myself with a professional food bag hang, again on a downed tree which created a perfect isolated and high bar. I take it down, do my business, have some food closer to the stream then pack up planning to stop again at an upcoming stream for second breakfast.

The pink light is unearthly, more like stage lighting in my private forest. I sing and walk along and suddenly, I feel a familiar kind of pressure in my chest.

Not this again!

My heartbeat begins to race and my body feels tired, like lead. I’m walking on flat ground and yet out of breathe, my backpack heavy and painful.

I move with slow, stumbling steps. I don’t feel well and I just want to stop. “Hey bear!” I yell feebly, my voice cracking a bit. “Bears of the for-rest!” I cross through a stream, and another, passing a tent I don’t recognize as any of my friend’s.

It’s an eternity to walk four miles, not really hot, just weighted from my being out of breath. When the trail rises slightly, I panic a little that I can’t keep moving.

By sheer will, I reach the cabin and crash on the porch. I take off my shoes and socks and lay them out to dry, then put electrolytes into my water and drink it all. When my heart races, I get nauseated and none of my breakfasts look appetizing.

But maybe something salty will. I make a lunch of fritos and an onion dip and gobble it up, starting to feel better in my little lair. The trees are huge here, reaching up tall and straight, puffy white clouds scattered on a blue sky.

I begin to perk back up enough to walk to the rushing stream for water, easily collected in a little waterfall. First I ensure my food is all packed up and I hang the bag on a nail before leaving.

It is a beautiful place, and coming up is a big climb to a ridge and finally the Chinese Wall, a massive piece of uplift like a curved edge of ship exposed from the ground and surrounded by other mountains in fancifully tipped shapes covered in snow.

Why am I suffering from this wild and sudden increase in my heart rate? What brings on this massive fatigue, dizziness and an inability to get enough air? I write Richard a note and tell him what’s going on, and that maybe I just need to rest here for a bit – or all day.

At first he’s supportive and gives me the encouragement I crave and never heard from the people I had expected would hike with and look out for me. “You’ve got this, love!”

I begin to cry, huge tears and gulping sobs. Why the hell am I out here alone and far away from Richard? I love what I see but I feel horrible both physically and emotionally. I write a note that tries to convey how much I miss him, to convey how sad I am that things didn’t work out with the friends we drove up with to the border and how deeply that hurts me.

His tone changes on the next message, worried about me and wanting me to make good choices. You have to understand that messages are not fast. We’re depending on satellites and sometimes they travel quickly, other times it can take 10, 20, 30 minutes to send.

He tells me that messages come out of order and don’t always make sense. I write that I’m feeling better now and will probably just rest here before heading up. He has this way of trusting my judgement even when he disagrees.

And yet he is not agreeing right now. Why, he asks, are the people you ferried to the start not walking with you in bear territory when that was all you asked of them, not for gas money or to share the hotel, just to stay close?

I’ve told him over the last several days that they go too fast and are 30 years younger. I cannot keep up. I also can’t get where they’re going if I don’t leave very early and walk alone. Somehow a huge chasm in communication has grown in these past two weeks and we don’t confer on plans at all. I took a different route which would be easier for me – at least I thought it would be.

So now, I’m not with them at all. I’m alone and something is seriously wrong. Maybe the people in the tent I passed will come and I can talk to them, get advice, feel more grounded.

I vacillate between packing up and going and setting my tent at this forest service cabin – even though it forbids it – and sleeping off this awful woozy weakness.

My heart has slowed and I’m feeling more like myself. I breathe in and out deeply, I enjoy the warm sun for the first time not just melting in it. I eat food and relax. I’m content.

And then, I can’t breathe. It comes seemingly out of nowhere. I’m gasping, drowning. My hands go numb and I’m light headed, dizzy.

Oh for god’s sake, am I having a heart attack? Has my body just given up? It’s in that moment I make a choice. No one is here to help me decide what to do. I don’t want to die in this place alone. I have walked strong and well but now my body seems to be rebelling.

I press the SOS.

“Emergency Response acknowledged your emergency. This is the IERCC, what is your emergency?”

I have to use my phone and bluetooth it to the device to write a message, it takes time and you only get 140 characters to state your case.

Perhaps I thought we could discuss things before they took action, so I ask for advice first. I tell them I’m short of breath, I have a racing heart, that I can’t stand up without feeling like I’ll pass out. Maybe I’m just tired? or hyperventilating? Is this what a heart attack feels like? I don’t know. Tell me what to do!

Of course their job is not to tell me to just sleep on it. I’m 30 miles from a road, alone in the wilderness. Their job is to get me out of there.

“Do not move and wait for rescue,” they say. Oh lord. Now I feel the whole thing has become dramatic and complete overkill. Richard tells me they’ve called him and I keep asking if this is even necessary.

The emergency services contacts the sheriff named Bill and gives me his direct contact. I write him and say the same that perhaps I just overdid it. But that message spins and spins in the ether, unable to find a satellite.

Richard finally gets through and we debate the merits of a rescue. I am laying on the ground, weak, nauseated, catching my breath in this beautiful place. The water is gurgling nearby, the wind in the tall pines and the air clear and fresh. It’s not hot yet. I am in the best place I can be. It’s heaven.

Richard tells me I can cancel the helicopter, but is that prudent? I am not just tired, I know that. My heart races on flat ground, my body feels like lead and I have to lay down, I’m gasping for air.

Still, shame wells up in me. Can’t I take care of myself? I am responsible for me and I should ensure I’m ok.

My shoes and socks are crispy now, my feet dry in my flip flops. I have all I need to wait and though my bad-assery can’t accept that I’m in trouble, I begin to see the wisdom in calling for help.

Richard writes that if I go on like this, I might collapse and then rescue might be too late. Funny, my hips and legs are strong but something else is giving out. I think of how often I’ve fallen on this walk. I’m not as nimble and feel not quite connected to my body, which I’ve bruised and lacerated.

I’m calm, not panicking, but I feel awful. Whatever this heart racing episode is, it shatters my body and sucks out all the energy. I use my bear bag as a pillow and lay on the ground. Flies buzz around me, some landing to lick up my sweat, but none biting.

I hear the chug-chug of a chopper and stand up to put everything tightly in my backpack. I tell them there is nowhere to land in one of my notes, but two helicopters – one red, one blue – circle seemingly looking anyway.

Red leaves and blue hangs in the air, a man emerging on a line rappelling down to the ground as the chopper hovers. Chris comes to me all business, ensuring I’m ok then putting me in a kind of large harness and placing a helmet on my head. He puts my backpack on his back and stuffs my phone, hat and glasses in his own bag.

This strong, blissful hiker limps over to the line still touching the ground below the helicopter. “I’m scared,” I say. “I’m terrified.” Chris is trained to ignore this and asks me to kneel, then attaches my harness to the line. I check my carabiner is locked.

He’s a small man, so I hardly feel him sit his body on my knees and we’re both hoisted into the sky, above my beautiful swaying trees, light, gentle, floating.

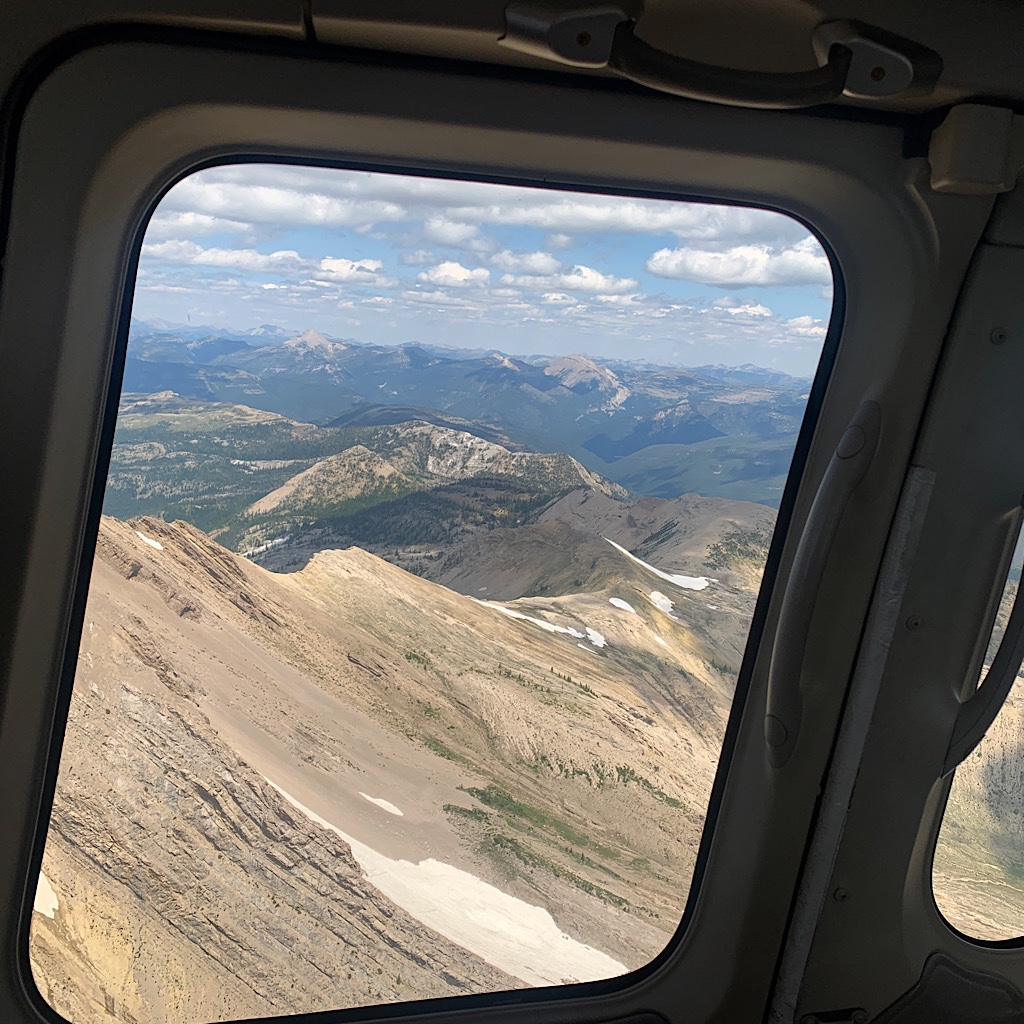

There’s a kind of landing pad that I’m sucked into where another man named Wil – with one L – hooks me to a different carabiner and pulls me in. The door closes and off we go.

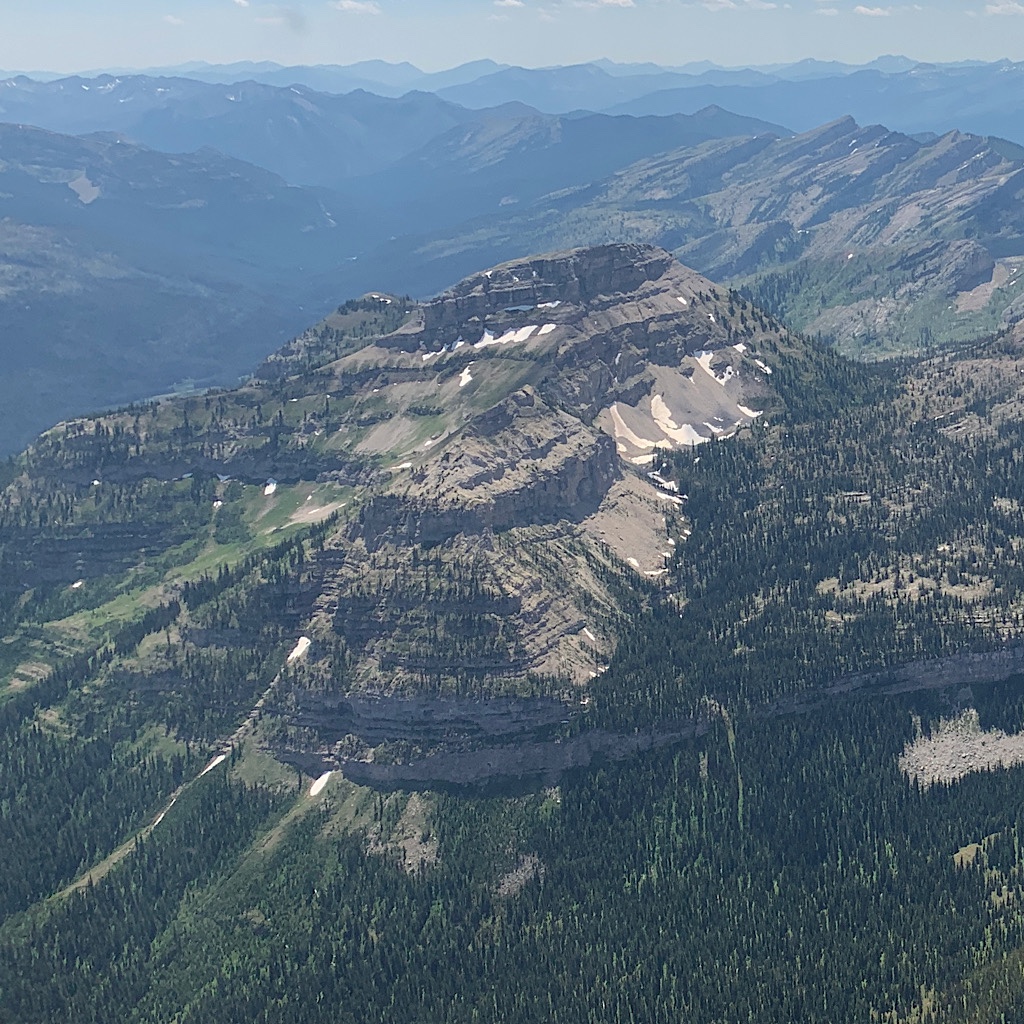

This was what I will not see from the trail. Massive mountains in uplifted and shifted forms of layered rock, snow caught in bowls, the trees a fringe below. The Chinese Wall! A reef of billion-year-old creatures, layered, pressed, cooked, squeezed into this glorious masterpiece of nature.

The land is like a carpet, snapped at one end leaving folds and ripples throughout. All of this is ancient as time, but appears alive, caught in motion as waves on the sea. It’s a better view from here than from the trail.

They give me a headset underneath an oxygen mask. As I ooh and ahh, they point to more views and I try to twist my body to see. “Not bad for Chris’s first long line!” the pilot quips. “Not bad for your first flight!” he quips back.

I tell them to shut up and laugh. They’ve got to be joking, I think. We leave the most spectacular mountains and arrive in a field with picnic tables and the red helicopter. It seems this is the life flight from Kalispell Regional Hospital with two EMT’s aboard. If they could have landed, I would have met them first.

Jason and oh, dear, I didn’t catch his name, meet me at the door, ask me my name and date of birth, then get to work, stabbing me with an IV and attaching electrodes to my chest. They can’t roll up my sleeves so ask if I can take off my shirt. I warn them I’m middle aged and get a laugh.

Everything is normal – ‘the blood pressure of a 20-year-old,’ heart rate of an athlete, plenty of oxygen in the blood, good color. Well, what the what now?!? They have me stand but I almost fall over. Kneel down, they say, and they’ll carry me on the stretcher.

That’s when I lose it.

Is it my bruised knees, my scratched and bloody calves, my absolutely shredded body from all those blowdowns? I can’t seem to kneel. I know I eventually find my way into that stretcher somehow and now it must appear I’m simply an hysteric, the hot sun blinding me.

“You guys look like pall bearers!”

“Only if your name is Paul!”

They lift me on the count of three, then slide me into the next helicopter. I say goodbye and thank my first team ‘Two Bear Rescue’ for coming for me, actually apologizing that this wasn’t necessary, that I wasted their time, making them promise they won’t talk badly about this stupid woman after they leave me.

There are views I see through my feet, mostly trees on mountains but also rocky peaks with some snow. I begin to gasp for air again, drowning in small sips. One of them tells me all is well with my body except for this ‘thready’ heartbeat, fast and narrow. They think I just didn’t drink enough, or my electrolytes went haywire. What a stupid person I am.

I finally calm as the Flathead Valley comes into view, wide and green. I ask again if I’m wasting their time. “Nah, I had to be plucked out when I was kayaking once and couldn’t get out.”

But embarrassment for such overkill floods my thoughts, even as we land and I’m wheeled into the ice cold emergency room.

Nurses hustle around me, the medics disappear and a collections agent hovers as they wheel me to a bed. Tracy pulls out my earrings and takes off my shoes, socks and pants. Tests are performed, X-rays taken, questions asked. I call home and Richard wonders why I pushed the SOS.

“This isn’t the nurse helpline!”

Finally Dr. Leonard comes in. They have real trauma to manage – a bleeding hematoma and some other dire emergency, but he’s patient with me. It’s not just nutrition, the heat or going too hard, he says you have an abnormal heartbeat.

Supraventrical tachycardia. Right. Well I know that, I get low on some vital nutrient and my heart races, right? No. It’s an unknown extra electrical impulse that sets the heart racing. My blood pressure drops to nothing and I feel heavy, gasping and ready to pass out. Oh, and if it lasts longer than a few seconds, my heart could stop.

Well there’s that.

Lovely.

He tells me to go home – or alternatively to hike with someone. “They’d be there when you pass out.” He then proceeds to share a story of a woman who broke a bone in The Bob, set it with her walking stick and walked out, all the way stalked by hungry animals.

At home, they’d hook me up to a heart monitor and come up with a plan, maybe medicine of some sort. Mostly people do vagal nerve stimulation like bearing down while holding the breath or putting your head between your knees, all in an effort to throw off that signal and switch things back to normal.

Other than that, I’m fine.

So, it’s not my hips, it’s my heart. My wonderful, healthy, got-me-all-over-the-world heart that’s got the problem, something he says shows up only in healthy people. Funny, my doctor heard something off about 12 years ago, but a cardiologist friend suggested I just drink more red wine. I guess not wildly off since it’s high stress that can often activate those rogue electrical impulses.

The debt collector is back to shake me upside down for the money I owe, even as I’m undressed lying in a pile of dirt I brought with me from the forest smeared into these sheets.

What will my insurance pay for? I’m out of state, using life flight transport and I suddenly think of all of those news reports of surprise bills and denied coverage. Richard and I talk again and he reassures me we’ll figure it out and that I did the right thing getting out when my symptoms kept getting worse and they couldn’t get to me fast enough to help.

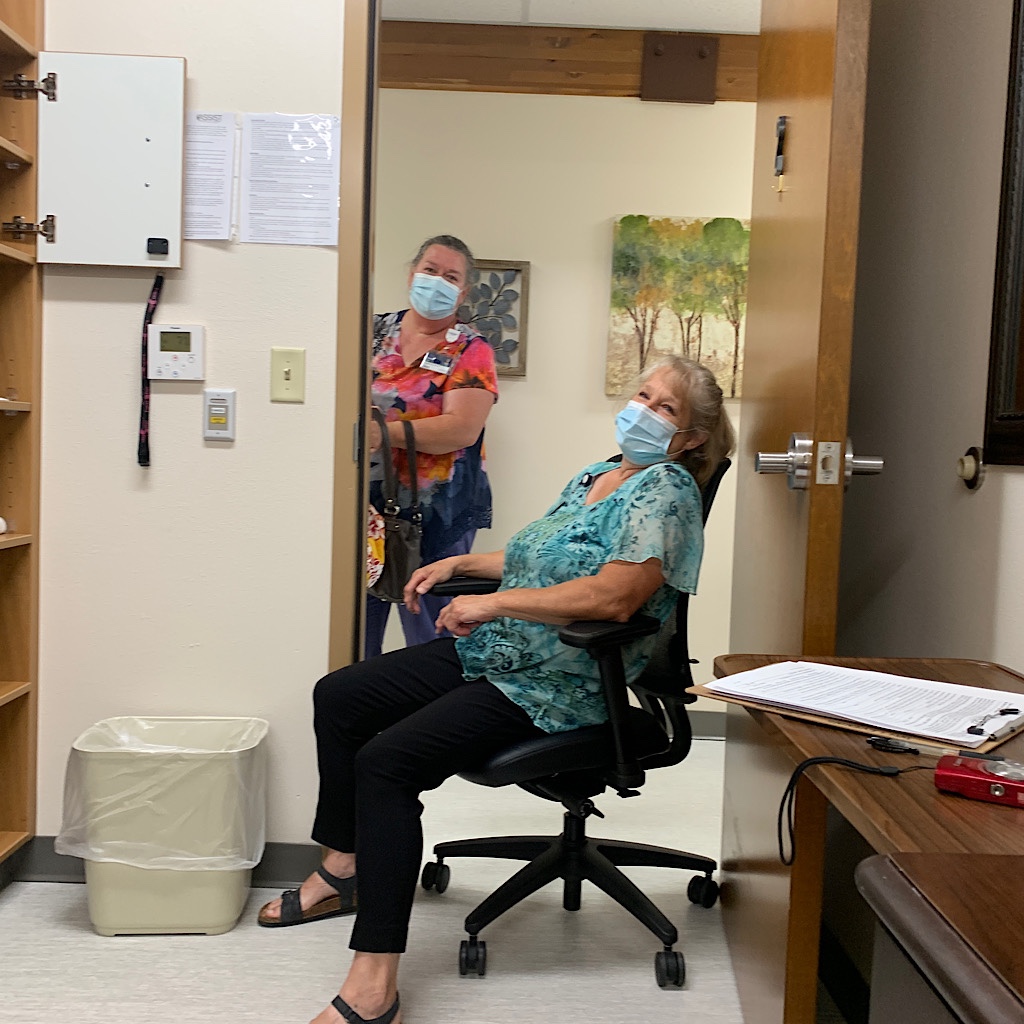

The hospital ‘trail angels’ me by putting me up at an assistance facility until I figure out what to do. There’s no charge for my little dorm room, a shared bath and a stocked refrigerator. Dawn’s on call and we hit it off right away.

So this SVT is a thing now, and really there’s no sense in second guessing getting off trail; it might have gone past the point of no return and I could have ended up a snack for bears. Funny my mother-in-law cracked a joke when Richard told her I could lose consciousness and needed help, “But aren’t you supposed to play dead around bears?” <groan>

Still, I’m pissed. Angry that I have more limitations to deal with, angry that I managed this without friends on trail, angry that I have to change plans. My brother shared a quote from Mike Tyson with me to cheer me up, probably paraphrasing it, but something like, “Plans are great right up until someone punches you square in the nose.”

He also compared my ordeal to the Tour de France. “Crashes happen, Al, and you’re going to have to improvise.” Ain’t that the truth. Looking back, I see gorgeous pictures and read my writing that expresses wonder and joy – but I also read about struggle. I was not enjoying it entirely, certainly not the group I was with or how hard it became when my heart raced or the intense heat that sucked the life out of me.

I’m stopped now and talking to friends here in Montana to see if it’s possible or wise to go forward with a complete reset. I have the gear, the provisions, I’m here and the trail awaits.

One young friend shares an ordeal with trying to ‘push through’ excruciating pain because that’s the culture she lives in as a ‘bad ass mountain woman’ then coming to find out she may have caused permanent damage.

Another warns me this is wild country and not only was a woman killed by a grizzly last week, but another is lost in the mountains, somewhere, no one knows where, even after they found her tent.

Still another suggests I hook up with artist friends and see a show, get myself around friendly faces. Her friend, a life coach, is convinced the universe is telling me to stop right now. She asks if I really want to die out here.

And then another tells me to get back on trail.

Whatever I do, I have to learn how to move and find joy within the parameters my body has set for me. I have to change tactics because I can’t hit the SOS a second time – and I can’t afford to feel like I did before: isolated, exhausted, incapacitated. I probably can’t be totally alone either.

The truth is resetting and entering the next phase with intention takes courage, to go outside expectation and write my own ending will require a clear focus, flexibility and a willingness to let go of what doesn’t work for me.

I don’t know yet what that will look like. I’m still tired and overwhelmed, but I’m safe and as they say, ‘the trail will provide.’

Perhaps something awaits me better than I’d originally planned, different for sure, but richer and more appreciated because my ability to do all things is slipping away. It may not be a thru-hike and it probably won’t be fast, it will be small steps, but I can do that much I’m sure.

Somehow that makes this bump in my journey, this learning experience of listening to my gut, making better choices and believing my body when it’s screaming for help, all worth it.

And perhaps in reframing and resetting, the very real possibility I’ll encounter will be to reconnect with my bliss.

24 Responses

Alison, reading about the experience, taking in the photos, and then reading the comments from the “ocean” of supporters, as someone put it, leaves me in awe. Is this the person I have known all of her life. Yes!!! I think you have exhibited courage and a kind of grace all along, even when life has thrown hard things at you. I’m proud to know you now, even more.

As one friend put it, keep writing so that the rest of us can be inspired. The journey continues. With love…

Alison, you are always journeying and taking us along with you through photos and narration, even on this last crazy airborne adventure. Sending good wishes and gratitude for your honest introspection that prompts us all to look more closely at our own lives. You inspire, Blissful Hiker. It is good to be alive!

thank you, Susan! So many challenges, but like the blowdowns, we just to face them head on.