Delay is never denial.

Lailah Gifty Akita

We’re up at the crack of dawn since last night’s party got a bit out of control and now we need to clean and pack before leaving Karen’s beautiful home right at the edge of the water.

Karen is a follower and a friend I have yet to meet who so generously gave me the run of her empty house on rocks above Lake Superior. She’s one bad ass gal, climbing Colorado 14ers into her 70’s. Karen is my heroine.

This vacation of hiking, kayaking, cooking and lazying around was desperately needed. But now it’s time to say goodbye as we busily vacuum, wash dishes and organize a week’s worth of garbage and recycling. Richard is grumpy without coffee. Sorry, smackles, it’s already packed.

The airport isn’t far, just up the hill where we pass our favorite field laid out like a table cloth, billowing out to the massive lake below. Round hay bales sit at odd angles like watchmen of the seemingly endless horizon.

This time though, after a week of glorious weather, we pass it under soupy skies, our height revealing just how dense the fog is sitting low on still water.

And just as you’d expect, the news isn’t good at the tiny Cook County Airport where one masked gentleman informs me the planes were grounded for two days. Just as the words leave his mouth, Isle Royale Seaplanes phones me to confirm what we expected – weather delay, though she cheerily promises to call each hour with any “developments.”

I surprise myself acting sanguine taking in this news. Perhaps it’s because Karen’s next guest won’t arrive for a few more days, so we’re not exactly stuck. Let’s just point out here that Grand Marais is a tourist destination. Not a bad place to be “stuck” in any case.

We drive into town and sip coffee and tea at Java Moose, me with the New York Times and a much less grumpy Richard playing solitaire, Artists Point reflected in the stillness. The paper is filled with analysis of the DNC convention with Facebook chatter at a high pitch. I read and snack and wait for my calls as the sun slowly peeks out, a silvery burst of light breaking into the mist.

Finally, at 2:30, Jon at Seaplane Central calls saying the ceiling is high enough now and it’s a go, so we hop in the car and head back up the hill, the sky getting bluer as we rise.

I throw my pack down in the shade next to the tarmac and Richard meets me, telling me he just heard the plane radio in. And here she comes! A sleek de Havilland single-engine Beaver rocking slightly as she steadies to land quickly on massive pontoons. This is her greatest attribute – short landing, then a quick taxi on miniature wheels like a rand piano being rolled on stage.

Two young kids hop out with dad following asking if they’d prefer to carry their backpacks or should he. Both yell back over their shoulders, “You!” I ask if they’re hungry and they assure me they were well fed by the resident rangers.

A woman walks up and hands the young pilot two bags of dehydrated meals, I assume to replace what the kids devoured of island provisions. It’s just a pit stop for gas, and two big steps for this solo hiker and solo passenger. Thomas takes my temperature and asks me a few questions about my health, and, even though we’re both masked, reminds me smoking is not allowed on board.

I’m so swept into the moment and utterly forget to kiss Richard goodbye. I don’t even thank him for such a wonderful week as we taxi towards the runway. I am so sorry, smackles. I hope you know I love you.

I know he landed fast, but I’m still startled by the short running start before we’re in the air, high above spruce bogs and undulating forests. The flight path leaves the shore right above Horseshoe Bay where Richard and I walked the secret mossy path on high cliffs to orange lichen-covered rocks above crashing waves.

Above the lake, I see Grand Portage where we climbed Mount Josephine and spoke with reenactment guides in voyageur costumes, stylish red sashes they explained to us used as weight belts to keep everyone’s insides together after carrying tump lined loads of over 100 pounds.

That’s also where we launched our kayaks and paddled to the witch tree, a ghostly cedar of twisting graying bark-less trunk except for one tiny strip of life feeding a wild head of branches. We thought we could cross to the Susie Islands and made a start for it until black clouds appeared over the mountain and a weird wind produced quartering waves.

Richard told me we were in a land of people who believe in signs and omens – heck, that’s what the witch tree is all about – and the sudden change of weather was telling us today was not our day to make an open water crossing in 45-degree water.

Our tiny plane is over this giant, cold body of water now, heading straight for Isle Royale, a mountainous strip of land 45 miles long. A pillow of fog remains, but far below and the water disappears only to reappear just as we arrive at Windigo, the deep finger-shaped Washington Harbor our landing strip.

Four backpackers are overjoyed when arrive as Thomas ensures I understand we’ll meet at on the other side of the island in eight days on Minnesota time not Michigan. All of this is very confusing since it was a navigational error that placed Isle Royale not only in the United States rather than much closer Canada, but as part of Michigan and not much closer Minnesota.

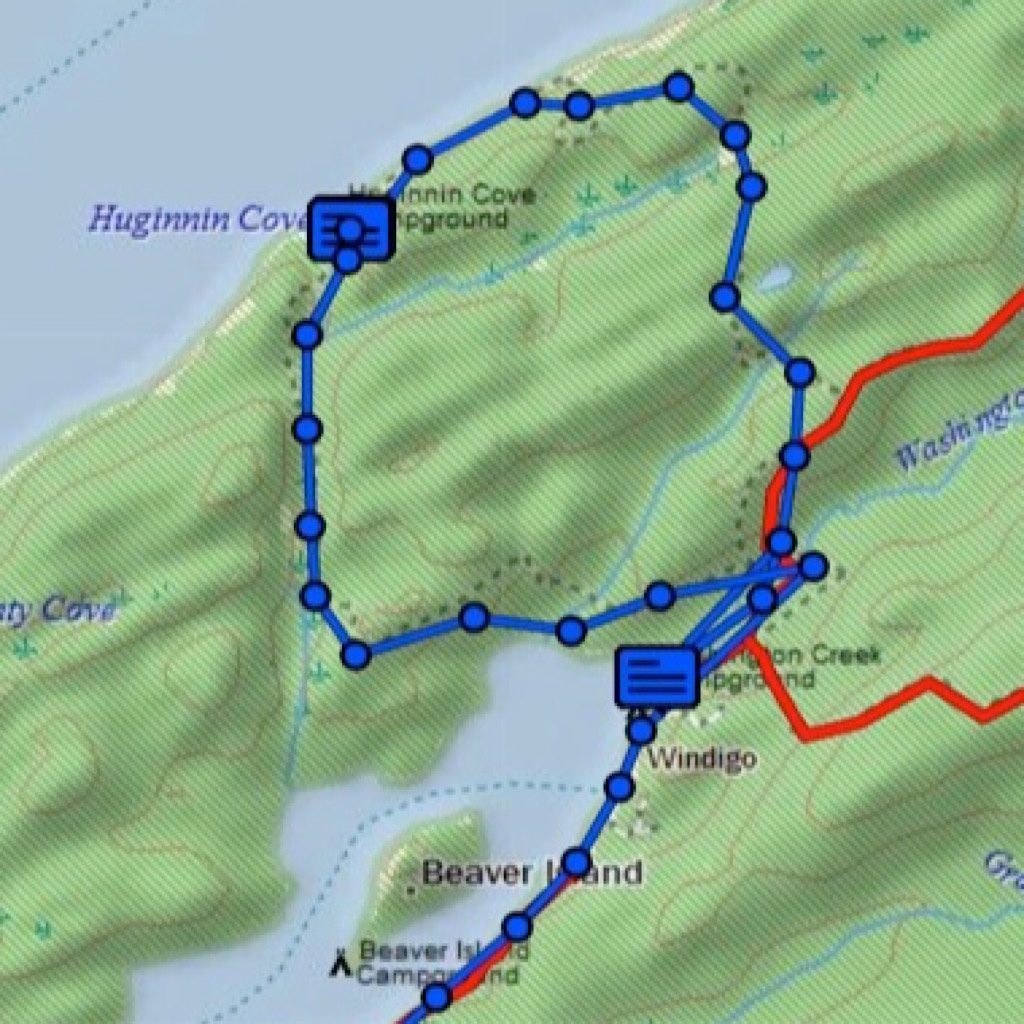

He hands me the fuel from a cage at the dock, gear I bought ahead of time then recommends with only limited daylight left, I walk the short five miles to Hugginin Cove tonight, even is out of my way, a cove that faces faces the sunset and Canada’s massive cliffs.

But first I need to check in at the ranger station for my permit and a lecture on LNT or ‘leave no trace.’ I pass a dozen or so backpackers, all stranded and waiting their turn to fly home on the tiny four-seater airplane. I feel for them – and for Thomas who will likely be flying until dark in this now perfect weather.

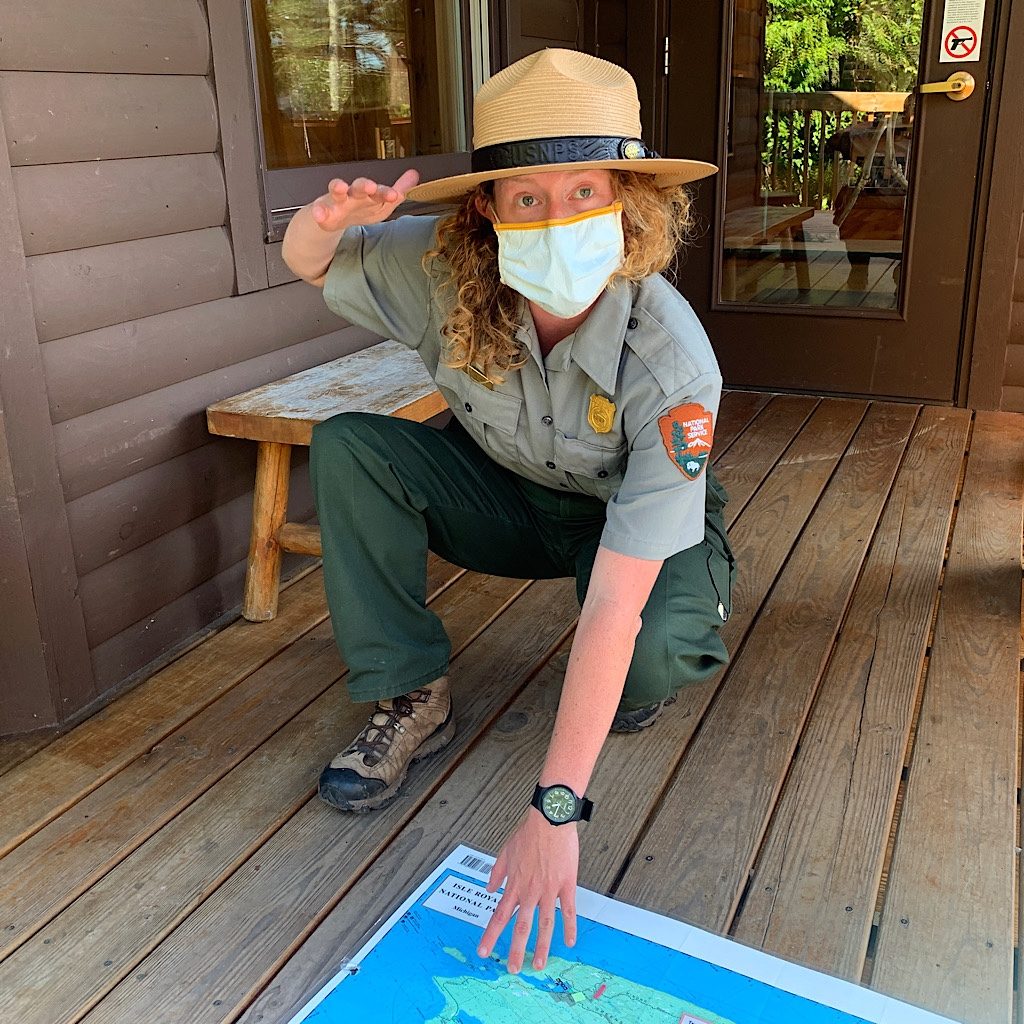

At the visitor center, a young curly haired ranger meets me outside. Both of us masked, we communicate our feelings with eyes and brows, crinkling when happy and widening when sharing something cool. We connect immediately. I am alone, so it’s just the two of us looking at a massive map where I share my sketchy plans.

The island boasts one of the longest closed predator/prey studies in the world between moose and wolves, animals that came generations ago likely crossing the ice. In recent years, the wolves fell victim to inbreeding and only two remained. It was decided – after much argument – to intervene by introducing wolves and there are currently twelve on the island, most wearing GPS collars and all tagged.

But those collars can get lost so to keep track, rangers call to the wolves. You might think you’re hearing a real wolf, but it’s just a good imitator howling in three stages, each successively louder.

She does note that should I hear a varying howl pattern, then that’s a bonafide wolf call – and I should take note and definitely report it when I reach Rock Harbor. She also suggests I report wolf tracks (especially if little) wolf poop, and any sightings, so I am on the lookout.

What I should also be on the lookout for are moose. There are 2,000 on the island and they can be quite aggressive. It’s too early for rut, but always a good idea to keep in mind that moose are far more dangerous than wolves. The best thing to do if I see one? Put something big between us. The ‘rule of thumb,’ I’m told, is to hold up my thumb and if I can’t block out the moose, I’m too close.

She then covers taking out my garbage, camping only in designated sites (due to a Covid and a small staff, cross-country camping is forbidden this season) leaving everything as is (except for berries!) putting out my fire completely and being considerate. Imagine this for a second: Isle Royale actually has quiet hours!

She warns me foxes will steal my shoes and the squirrels will eat my food, so pack up tight at night. I ask where they came from and this time both sets of our eyes grow big in wonder. “That is the mystery!” A boat? Dropped by a predator? She then tells me the island has garter snakes with unusual markings unlike any on the mainland, salamanders and frogs. This is going to be one cool hike!

By the time I leave, we’ve charted a course and planned my campsites, though I’m always free to be flexible. And like that, I’m off though in typical fashion, I immediately take a wrong turn into the campground.

It’s fairly easy at the start on beautifully built narrow wooden walkways over wetlands teaming with insects. There’s a tiny bit of up and down in a green tunnel of loaded thimbleberry bushes – plump explosions of sweet and tart.

It takes time for me to find my rhythm as I remind myself this is a very small thru-hike, one I can relax on and let go of any gotta-get-there feelings. The air is perfect – not too warm or too cold, though quite humid and I’m already sweating.

I graze as I go arriving at the cut off for the Minong Trail, closed this year due to Covid. The most remote and strenuous of the trails, a search and rescue can take up to 16 hours and could be further complicated should the team need respirators. I was disappointed not to walk it this time, but where I am now challenges me enough.

I pass a turnout for an abandoned mine, but only see remains of a log building. Minong is the Ojibwe word for this island and has been mined for its pure copper since the pre-contact era. I’ll see more mine remains as I move east.

Long, thick boards take me past a marsh of light brown grasses, the water spilling out below me. More thimbleberries reach as high as my thighs offering their fruit in embarrassing quantities. The young ranger promises an even bigger haul as I walk since the other side of the island is slightly behind in the season.

Birch and spruce change to cedar as I approach the lake, sidling the shore over rocks and roots. A fishing boat bobs in the water nearby and the sun burns hot in reflection. Thimbleberries give way to blueberries bunched close to the ground, plump and juicy. Canada’s ridges in dark blue seem to rise from the shimmer.

I come to a mossy boulder a bit high to climb up, but I notice a smaller rock next to it and decide to use it as, quite literally, a stepping stone. I step up, using my stick to balance, but it fails to make purchase and my foot slips down fast in the crevice between the rocks, folding on itself in a wedge.

Yow! That did not feel good at all. I put my weight on the foot, recalling the time in New Zealand I wiped out thinking I cracked the bone. I’m fine walking, but I can feel a bruise swelling under the skin.

The campsites are close and I know I can soak my foot in the frigid water, so I move along more carefully, chiding myself for not being more careful. An injury is absolutely out of the question, I simply cannot fall. Was I being clumsy or careless? I’m not feeling as strong as usual, but I stop myself before I crawl down that hole of non-stop criticism and thank whoever was looking out for me and keeping me from breaking bones.

As I approach the tiny bay, I see tents set up with a few people staring our into the view, motionless and absolutely silent as though at a religious service. I’m surprised and delighted after all the party atmosphere of the PCT. Coming around the curve, a sign shows me the five sites and, more important, the whereabouts of the outhouse.

The sun gets closer to setting as a beaver swims across. Sites four and five are empty, but awful, tucked deep back into the woods with poor water access. I cross a bubbling stream as crows flap noisily past and a squirrel chatters above.

Wait a minute, the tents were next to these, that means they must have been in sites two and three. Where is site one?

I head back, crossing the stream and passing the tents to see the small sign for site one I must have missed coming in. The thin trail takes me along the water on crunchy pebbles then over some downed trees. I see a bench through the curtain of trees, and, glory halleluia, no tents!

What a perfect site, the orange light of the setting sun glowing on a flat spot big enough for the alicoop. I set quickly and throw everything inside, changing into my camp tee and flipflops, then head to my private rock verandah. A lavender-mauve sunset accompanies my dinner, my injured foot submerged cooling the half-dollar sized bruise.

A sliver moon hangs in the sky gradually sliding from white to orange as it follows the sun over the horizon. Dragonflies hover next to me, feasting on gnats as beavers slap the water like cannonballers.

What force made this magic happen? Saving site number one for me, keeping me from a more serious injury, putting a perfect pair of hiker pants with a plethora of pockets on the rack at the thrift store just when I walked in, that sent me on my flight later today so only a five mile walk was doable and I could get here in this glorious little cove?

Maybe it’s not by design, but just a magical coming together of things and the secret is being open enough to notice, and equally, alert enough to be full of gratitude.

4 Responses

I am so delighted to hear that all the stars aligned and you made it to Hugginin Cove! It sounds magical how it all came together. Love following your journey, and having this shared experience of hiking Isle Royale this season. Listened to the Pee Rag episode as well and it’s captivating.

thank you, Jamie! It was you who gave me the push and I’m SO GLAD! Hugginin was cool. 🐥👣🎒

Love, love, LOVE this!! I’ve been so overwhelmed by Colorado this summer that it was a great reminder of what I’ll be coming home to in October! The photos of the berries and the sunset are super. Nice to be on a hike with you again!!😘

thanks Karen! It was so wondrous, so much more like being invited into a wilderness wonderland with so many creatures. I’m sending the stories in installments, so more stories to share 😉 This winter bringing my snow shoes to GM, so look out!!