Located in New Hampshire’s White Mountains, the Presidential Traverse is a 23-mile, 9,000-foot elevation gain/loss, continuous hike that summits ten peaks named after American presidents, including the highest, Mount Washington.

A friend I made on one of my adventures died attempting a solo traverse of the Presidential Range in winter. So heartbroken that this happened to someone with such vivacity and strength, I felt I needed to go and see the place for myself, pay my respects and walk the rest of the trail for her.

I had no idea what I was in for. These are mountains to be respected. Stretching only twenty miles, and easily accessed by major roads hardly captures the remoteness and danger of this wind-ravaged wilderness. A walker climbs close to 10,000 vertical feet up and down over the exposed expanse with few escape routes.

I joined my friend Randy for the traverse one early August morning, setting a fast pace up the rocky and steep Valley Way Trail. At a little over three miles before it breaks out of the trees, a stern warning tells the unprepared to turn back if the weather looks bad as people die here even in summer. We pressed on into sunshine and light winds, pausing at Madison Spring Hut for a snack before climbing up the boulder-strewn path to Mount Madison. From here, I could easily spot Star Lake where Kate’s frozen body was recovered. I left a photo and a prayer in the huge rock cairn atop the mountain.

As we were carrying camping gear, we decided to take the longer, more circuitous route up Mount Adams stretching along the narrow slope of the Gulfside Trail and finally a rock hop up to the summit. From here, all of the peaks stretched before my gaze including Mount Washington, where the second fastest wind speed in the world was clocked at 230 mph.

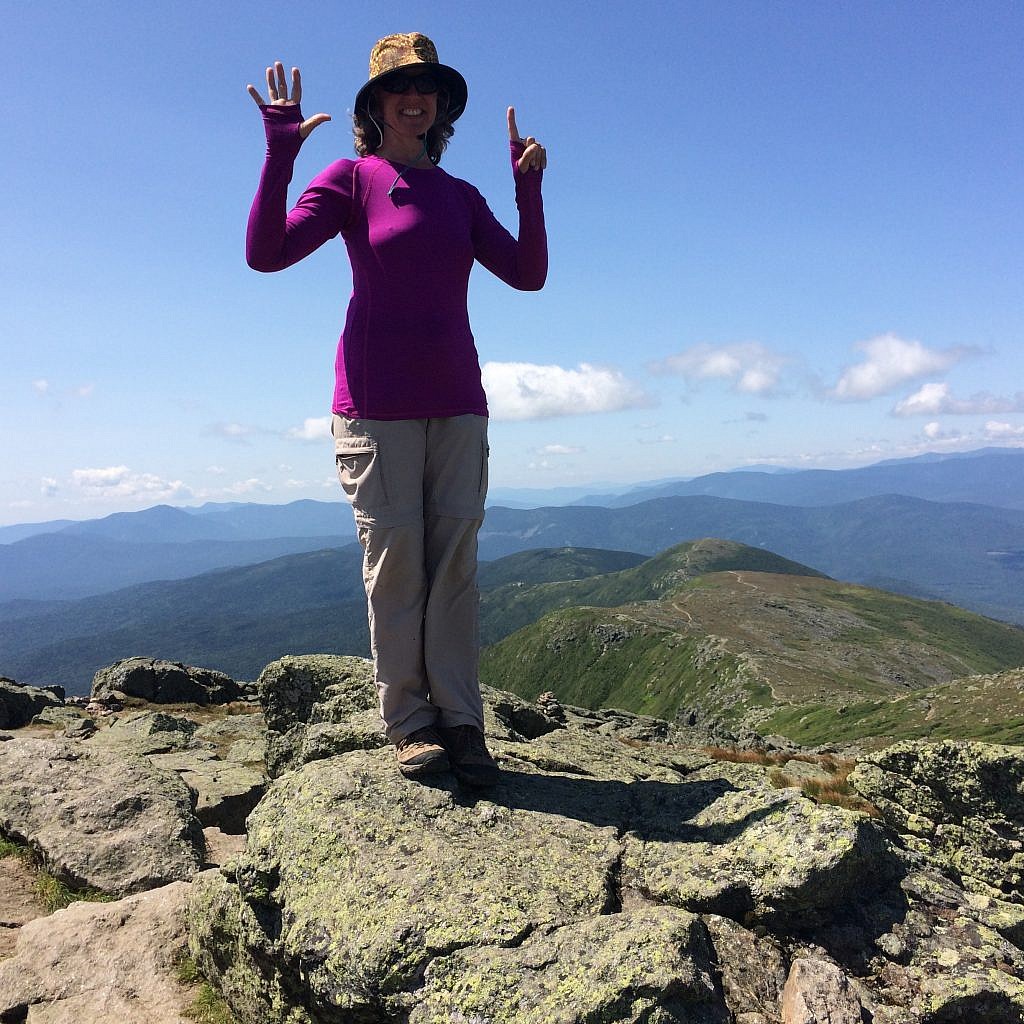

Then it’s down a huge rocky gully where I wasn’t so much winded as constantly watching every footfall. Down and down, and then down some more, losing nearly all of the elevation I’d gained, then back up onto the lush cairn-decorated Monticello Lawn before pressing up on boulders again to the airy top. Here I had to don my rain jacket as the clouds began to build and storms appeared imminent. I lingered only long enough for a picture

It was one of the most beautiful walks on a kind of tundra towards Mount Clay, stunted spruce and tiny flowers clinging tightly to any dirt between lichen-covered stone. I was feeling happy and relaxed here as I looked straight up Mount Washington’s bulk. I said to Randy, “Oh, I think we should crack up Washington. That storm’s not coming…” but my last word was cut off by the loudest, most vicious crack of thunder you can imagine directly over the path we had just walked.

That was our cue to run – and fast. I was under the misconception that we could seek shelter under the large rocks, which Randy explained was about the most foolish thing we could do as rock conducts the electricity. There was no way we could go up, and there was no trail down, so we simply pushed low and squatted into the shrub trees. We tossed our hiking sticks to keep any metal far away and just waited it out. Downpours of hail and fast rising misty whiteout followed dramatic streaks of lightning.

Randy admitted he had always wanted to sleep in the dungeon at the Lakes of the Clouds Hut. I had no idea what he was talking about, but at that point, the temperature was dropping and it was time to make our move. We skirted Washington, pushed under the cog rail and soon spotted the lakes nestled in a bowl.

The hut was full – as was every floor space taken up by AT thru-hikers. But two bunks remained in the dungeon, a space built for lost hikers in winter who hope to avoid missing their escape route in a blizzard. The very basic set-up looked like a concentration camp and smelled of bug spray, but it was safe and warm as the wind picked up to 60 mph giving the swirling mist a ghostly feel.

I slept well and the morning broke to crystal clear skies. We retraced our steps, but then pushed around the mountain on Boott Spur to take in some of astonishingly huge Tuckerman’s Ravine. All along the trails were gigantic cairns, that seemed unnecessary in such placid weather, but are life-savers when things turn.

At the observatory, we ate some real food with the mass of tourists already up bright and early, and took in the many exhibits on weather patterns. On one wall was a list of all who lost their lives on this treacherous mountain range, including Kate’s. What caused her to keep going that day and not turn back? When did she know she couldn’t make it back in those winds? She was tough and driven, but no one could have survived that day. I wept for her and those she loved.

After Washington it was down and down for a few pimples of mountains compared to the drama of the day before, Monroe, Franklin and Eisenhower. The trail goes on, but at this point, it was time to go. We said goodbye to this range of 4000-foot peaks. Low by Colorado or Himalayan standards but filled with beauty, ruggedness and danger.

Randy ended up hitching a ride back to the car, giving them a story about his sick wife to convince them to take him the whole way. While I waited at the hiking center I thought about all my prejudices to hiking “back east” and how in that stunning two-day traverse, all of those pre-conceived notions were knocked out of me.

But there was no rest for the weary, Randy and I hiked some more in that week in New Hampshire – Franconia Ridge, Mount Moosilauke and the Bonds, where again we got caught out on a high ridge with a fast moving lightning storm directly upon us. It was some of the most exciting hiking I have ever done and I’d go back in a heartbeat.

9 Responses

Alison-

My wife and I now live in Denver but we lived most of our lives in the Boston area and hiked the Presidentials in summer, fall and winter. I am now 86 but seeing your images and reading about your climbs make me homesick. Thanks

Tom A

The Whites are such a special place. I hope it’s homesick in a good way 🙂