The lake is the boss.

—paddler’s mantra

A few years ago, Richard and I took our kayaks to the North Shore of Lake Superior. We planned to visit a stunning set of thirteen uninhabited islands called “The Susies” right at the Canadian border and a short two-mile paddle from Grand Portage. I’d seen them from the top of Mount Josephine, 750 feet above the lake, spreading out like emeralds on a turquoise bed.

The weather was expected to be ideal – calm, clear skies and warm, at least as far as the air temperature. The lake itself is notorious for its frigidness, reaching only into the upper 50s in summer. A paddler needs to wear neoprene or a dry suit and be skilled enough to get out of the water and back in a tippy boat should they flip. In cold temperatures, that means there’s little time before hypothermia sets in. So even on a hot day, you need to work fast. While I never quite got the hang of an Eskimo roll, I’d practiced “wet exits” over and over so felt confident I could manage.

We rounded Grand Portage Bay where the replica fort sits on Ojibwe land to find a launch at the north end of the bay and at the base of a peninsula separating this bay from the larger and less protected Wauswaugoining Bay. That’s the one we would cross to get to the islands and that’s when things started to go wrong.

As we gathered our gear, someone drove in to tell us we were not allowed to park here and in fact needed to pay for parking at the marina. I was already suited up and our kayaks were sitting on the dock, so he allowed us to launch but we would still need to go back to the marina half way around the bay.

Just as I we got back in the car, Richard told me he forgot his wallet and somehow, his gloves were missing too. I had money so did the paying, but these little mistakes started to niggle at us and we ignored changes in the atmosphere, like the wind building and the pressure dropping.

We finally set off, but as I closed my hatches I realized I’d forgotten our lunches. Now we were really feeling uneasy. Nonetheless, we set off in smooth water around Hat Point, a spot Voyageurs looked for as a conclusion to their long trip across the Great Lakes. Just as we came around the point, wind smacked us from the side.

So much for the weather report.

What looked like an easy 45-minute paddle from above, at the vantage point of a low-profile watercraft, was really an enormous, exposed stretch of confused waves all the way to fuzzy land far in the distance. Instinctively we hugged the shoreline, thinking we might follow it before committing to a cross. Just that small change in direction brought us face to face with the vertical basalt cliffs of Mount Josephine and what until now was hidden – an ever blackening sky.

A mantra many of us kayakers use is “the lake is the boss.” We might be able to fight these waves going out – or continue following this shoreline – but what if the waves build? Are there any safe places to exit?

Today, we both realized, was not our day.

With some difficulty as water cold and harsh crashed over our bows, we turned around and quit the cross.

Predictive Processing Framework

At the risk of getting too woowoo, I want to talk about gut feelings as a road to deeper awareness, an awareness that might cause us to quit while the quitting’s good.

Forgetting the gloves and the wallet, parking in the wrong place and having to backtrack to pay, then realizing we’d left our food at home felt to both us like omens. They activated our intuition that something wasn’t right and we felt it in our bodies.

But quantifying decisions based on feelings often gets a bad wrap. We ought to be more analytical, the argument goes, surely we’ve progressed beyond relying on magical or religious thinking to make rational decisions.

The problem is that emotions are not simply whimsical and fallible tools disconnected from the processing centers of our minds. They are deeply connected to them. In fact our emotions help us understand situations and ultimately make decisions. Scientists call this the “predictive processing framework” where the brain operates more as a (probabilistic) prognosticating machine, comparing current sensory information with stored knowledge and memories, then generating models to better understand a current situation.

But what about that “gut feeling?” Intuition is often described as something that happens quickly, automatically and in the subconscious, while analytical thinking is more logical and deliberate. It has often been thought (intuited?) that analytical and intuitive thinking happen together like a seesaw. But a recent study shows them to be uncorrelated, meaning they could happen at the same time. The brain is processing so fast, we’re not aware enough to make judgments and when something “does not compute,” signals are often sent to our innards. We quite literally feel feelings even when we’re not sure why.

While sometimes our past memories can make a mess of things – just think about how nervous you get at the prospect of public speaking – the physical sense that something is not right, what neuroscientists call interoception, can slow us down enough to take the time to analyze things more thoroughly and make a better decision.

Richard and I did what we thought was a thorough check of our gear, our skills, the route and the bail out options and yet we still made mistakes and didn’t have all the information. I find it interesting that the mistakes were not in and of themselves trip ending, like forgetting a paddle or finding a leak in the boat. It was the sinking feeling in our gut that prodded us to be more aware, to look up and around and eventually see the menacing building squall that was hidden behind the mountain.

read next Quitting is believing in Abundance

Three Strikes, You’re Out

A week after this happened, I ran into divers on Isle Royale. These weren’t your run-of-the-mill recreational divers. They were technical divers, visiting shipwrecks in frigid water at depths of 300 feet and breathing a mix of nitrogen and helium to be able to stay underwater for hours at a time. Skill- and gear-heavy, technical diving is dangerous, oftentimes with no second chances should something go wrong.

As we lounged on the dock, I struck up a conversation with diver and photographer Jeff Lindsay. I mentioned our kayaking debacle and he told me he has his own rule of thumb about quitting. If he has just three small issues that go wrong, he’ll sit things out, even though it’s a difficult decision to make after spending so much time and money.

In a conversation more recently, he told me,

I’m...a strong believer in the ‘little voice of reason’. I’ve called a dive simply by not having a good feeling. I could not point to anything specific, just a general uneasiness that I could not shake. Any “big” dive always gives me butterflies in my stomach. I equate this to heightened senses and respect for what I’m about to do. This is different feeling, something like a problem that I’m unable to properly articulate but know it exists.

He went on to say that after losing friends to this sport who he’d respected for their skills and sober decision-making, he began reflecting on his own limitations. “No matter how good we think we may be at something, the limitations of what we are capable of can change on any given day. Honest brutal truth with myself is important.”

How he takes these thoughts beyond risky activities and into his daily life was an eye opener.

I’ve seen that taking short cuts often doesn’t immediately result in severe consequences, which I think is incredibly dangerous. Eventually the short cuts become bad habits and sooner or later that deviation from a proven system that works will result in a problem. The severity of the problem is then up to luck as to when and where it happens, a less than ideal situation.

read the Q&A with Jeff Lindsay

There’s an old adage: ‘The heart wants what it wants.’ Yeah, sure…but even more powerfully: ‘The gut knows what it knows.

—Elizabeth Gilbert

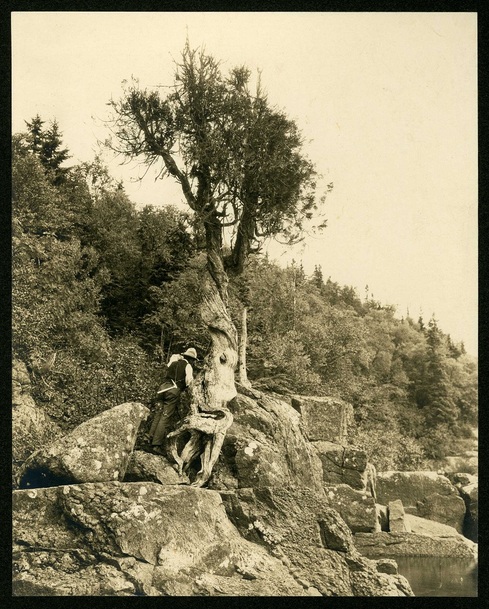

Right after Richard and I turned around, we found a small cove, not more than a divet in the rocks, that protected us from the wind and waves. It was there we came upon the Witch Tree. Manidoo-giizhikens, or Little Cedar Spirit Tree is sacred to the Ojbwe of Northern Minnesota. Gnarled and stunted like a bonsai this 300-year-old Eastern White Cedar appears to be growing right out of the rock. Tobacco and ribbons were tied to her base, gifts given to ensure safe crossing of Gitchee Gumee, the Big Sea. To us she appeared wise, even welcoming and we were humbled by our hubris in thinking we had the power to manage the lake.

It began to drizzle and we pushed off the rock paddling back into the waves. As we rounded the point, rain and mist blew into our faces, making it difficult to see as our kayaks bucked and bounced on the surf. Just ahead, two men jumped into an open canoe and began paddling. On the verge of swamping, they moved fast seemingly guiding us back to the dock before they disappeared in the white out

“Did you see them?” Richard asked as waves buffeted his kayak making disembarking tricky on a cement ramp. Of course I saw them, but who were they and why were they here?

We put the kayaks back on the car and changed out of our damp clothes, studying the map for a protected bay further south that we might explore to make up for the loss of our planned adventure.

As we drove, we were silent in a kind of spooked stupor. Richard finally broke the silence saying we had been kayaking in the land of a people who put great trust in signs and omens. They would have listened carefully to what their bodies told them before putting themselves in possible danger. Then he wondered if maybe those two men were sent by the spirits to usher us to safety. I don’t know. I don’t really believe in that. But it does make you wonder.

Elizabeth Gilbert wrote, “There’s an old adage: ‘The heart wants what it wants.’ Yeah, sure…but even more powerfully: ‘The gut knows what it knows.'”

Quitting that day was a powerful lesson in letting my gut be the boss – oh, and also letting the lake do its job by being my boss’s boss.

This is part one in a series about intentional quitting as a force for a more positive and fulfilling life. Read more: Quitting is Optimism, Quitting is Saying Yes, Quitting is Believing in Abundance, Quitting is Awareness.

4 Responses

I grew up on the shores of Lake Superior’s Chequamegon Bay so I am well acquainted with the lake’s fickle ways! I recall a day my dad and I were heading out in our 18 ft. Thompson boat for a day of fishing in the Apostle Islands. We saw three sizable men heading out in, to us, a boat not up to Superior’s requirements. Their craft was perhaps 14 ft. and overloaded. They were not from town and were obviously oblivious to any danger. Just a day of fun, fishing on the big lake. I felt a sense of foreboding for them; for their ignorance and lack of respect for the lake. Later the wind came up and a chop developed. Our boat was good in rough water, but it was choppy enough to make it difficult. We decided to call it a day and headed in. The next day I read about a boat with three men in it that had capsized the previous day. Two men drowned after clinging to the hull and one survivor made shore, clinging to a seat cushion. He described seeing our boat and a Coast Guard cutter out of Bayfield that went by close to us. There was a Coast Guard sailor in the bow scanning with binoculars. We never saw or heard them. I’m still sad, thinking how we may have been able to save them.

oh my gosh, John. This is such a tragic story. I was out with three friends in the Apostles when a family of five decided to go out on one sit-on-top kayak. They were swamped and several killed. We heard about it when we came in. Shocking!

What a story, well-told and with an important point to be heeded. I’m sure most of your supporters who read this blog could recall times when they felt the same uneasiness. I know I have. Thanks for giving me more insight into why we should pay attention to what our “gut” is telling us.

Thank you! While I was reading more about how our intuition actually communicates with the gut, I was intrigued. There’s a book i read many years ago called “The Gift of Fear” and the author spoke about how we can pick up incongruities subconsciously, “out of the corner of our eye,” and have a feeling something is out of order but cant quite put our finger on it. I have felt this before while walking and turned around to sometimes see something following me!