My dad has given me the best gift anyone has ever given me. He gave me wings to fly.

Adria Arjona

There’s a lot of things my dad and I share – a Roman nose (inherited from his mom, Janet Loricchio) an addiction to Gummy Bears (which his wife, Ding, calls his “antidepressant pills”), an outsize passion for classical music, ready smiles that crack up our faces into a mass of crinkles, and a love of the outdoors that oftentimes brings us to tears.

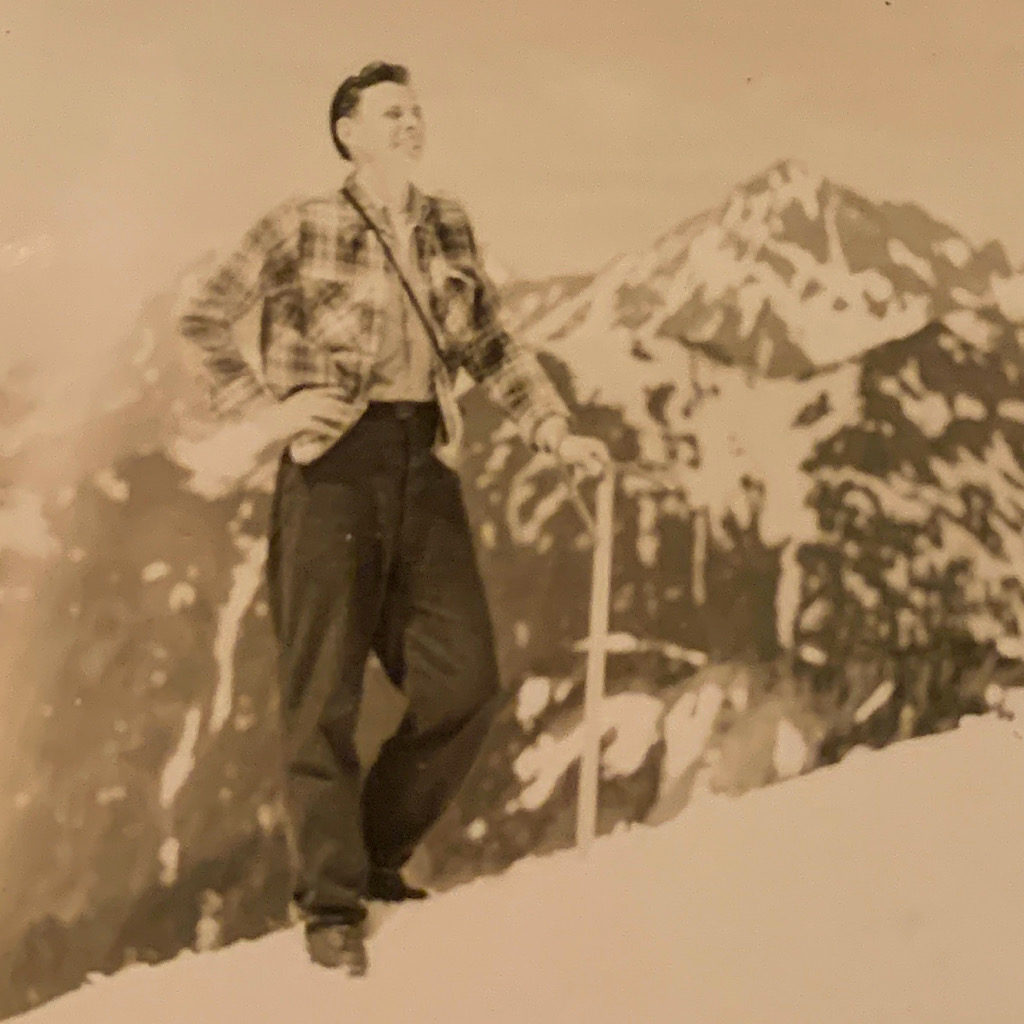

At fifteen, my dad left the nest to blaze his own trail, and ended up in Bellingham, Washington working in a men’s clothing store while finishing high school. He enlisted in the Navy, to see the world, but always kept his feet on terra firma as much as possible, especially in the fresh air of the North Cascades, a wonderland of deep green touched by fingers of snow late into the season.

There’s a wonderful picture of my dad in those mountains posing with his ice ax, never realizing it would take me five decades to get to this very spot when I walked the Pacific Crest Trail last summer.

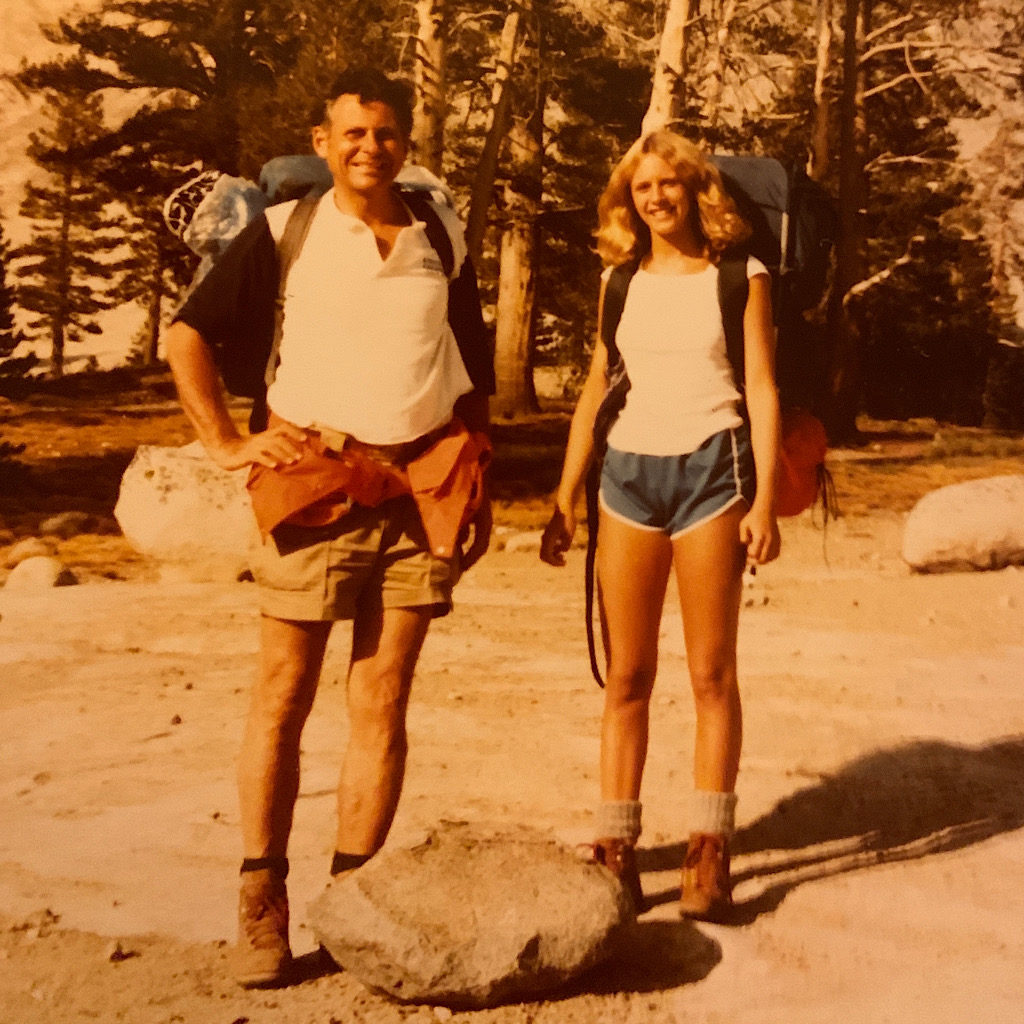

I wouldn’t describe Paul Young as a “backpacker,” per se. He did heft a pack and slept in a tent in the Trinity Alps in Northern California and shared a few nights with me near Cathedral Peak in Yosemite when I was 15. We carried cans of Dinty Moore Stew for dinners and slept “cowgirl” style, shivering most of the night under a canopy of stars.

No, my dad is more of an explorer who’s managed to fit in some spectacular walks into his world-wide travels. One summer, he hired porters and a guide to walk him up to Fairy Meadows, a place as enchanted as the name suggests, hanging below silvery glaciers clinging to the side of the 8,000 meter peak Nanga Parbat in the Karakorum. He just happened to be in the neighborhood working as a diplomat in Islamabad.

Another time, while leading a group of tourists through the Middle East, he slipped away one morning then slipped a few piasters to a guard who looked the other way when he climbed to the top of each (climbable) pyramid in Giza. He describes it as just some very big steps, just don’t look down. I’m pretty sure he squeezed this adventure in before they shut that down.

On a long transatlantic flight, my dad’s seat mate noticed he traveled with a rucksack and boots. His companion suggested he check out a route in Norway that is skied from hut to hut, then spent the entirety of the flight giving dad instructions and details on how to make it happen. With all that effort, there was pretty much no way dad wasn’t going to follow through and found himself on one of the finest treks of his life.

Dad told me just this past summer when he took me out for sushi after I finished the Pacific Crest Trail that the Norwegians use the term “wander” for hiking. The term resonates with both of us, inner directed people who are driven towards our goals, yet happily making space for the serendipitous.

The words ‘hiking’, ‘trekking’, even ‘tramping’, sometimes feel too aggressive, like the experience of moving our bodies through a natural setting is purely physical. ‘Saunter’ is my favorite word for what I do, since I move slowly enough to see and notice things, but ‘wander‘ introduces a whole new level of the psychological space one enters, the openness to the new without any agenda and little care of success or failure, because the simple act of going out in nature is enough.

It’s always a blessing when we realize the very moment something life-changing is happening to us. I was 13 when my dad decided he’d had enough of Michigan and wanted to return to the West Coast. So he flew my brother Andrew and me out to Los Angeles to begin a summer of interviews and a little bit of our own “wandering.”

I loved the beaches, Catalina Island, San Francisco and Disneyland but when we drove up the narrow mountain road to Yosemite Valley and I saw the view made famous by Ansel Adams, I felt like I’d come home.

Yes, Yosemite is magnificent in every way from the hush of wind in the pines and crash of falls, the fresh, dry air under crystal skies, the pungent piney smell and the solid touch of granite under the feet.

But for me, the life changing moment was in how I felt moving on the trail. It was a combination of realizing my own strength and power as well as a sense of freedom in being able to take myself from one stunning viewpoint to another.

We were spending all day in this glorious playground, and then driving two hours each way, far down the canyon to sleep at a friend of a friend’s cabin. If there was even the slightest chance we were going to create space to wander and allow for the serendipitous, this arrangement needed to change.

And dad pulled it off, working out a ride to Glacier Point where we’d walk past the most famous falls, spend a night at Little Yosemite, then climb to the top of Half Dome via chain ladders.

It would only work if we could figure out a way to carry our gear. Without a single complaint, dad organized the duties – Andrew would carry our one large backpack with spare jackets, the infamous Dinty Moore Stew to share and a sleeping bag crammed deep inside, while dad carried the other two sleeping bags on their own, by simply gripping the openings.

It wasn’t that they were heavy or anything, but I’m sure it was extremely awkward – and we likely looked like total idiots. But this was 1979, way before the rise of tech gear, and no one said a thing.

And me? Well, I carried my flute in a tiny school bag – another one of my dad’s ideas. “Play a tune for us, Alison, won’t you, on top of Half Dome?”

And that’s exactly what I did.

So here’s a Happy Father’s Day tribute to the guy who helped me put my feet on the trail and find my calling – even if now I use a backpack and pretty much avoid the Dinty Moore.

Thanks, Dad!

13 Responses

I thoroughly enjoyed this Father’s Day essay. It made me stop and think about what my Dad did that made me who I am today. I bet every reader did that to a degree. This was a gift to ALL Fathers, not just Paul Young!

yeah, dad’s can sometimes really rock. he bought me my first ‘pro’ flute too

It is wonderful how certain events and people can have such a profound influence on one’s life. You are so lucky that your father shared and infected you with his passion for the hills and exploration.

I am so lucky and we shared our ‘war stories’ just this past Sunday! Lots of ones about avoiding black bears!

Alison, this is such a beautiful tribute to your Dad. Thanks for writing it down with such eloquence. There’s a lot of detail I never knew. He has left you a legacy that has changed your life. He should be very proud.

thanks MD! I am so impressed that he just made the overnight Half Dome trip happen even when we had the wrong gear. The memory never left me and is part of my current hiking philosophy! 🐥👣🎒

Good conversation!

I can imagine the wandering trail!

yay! #neverstopwalking #onestepatatime #paintopower