“Do you ever hike with Richard?”

A lot of people ask me if I hike with my husband, Richard. The answer is yes and no. Wearing the same clothes day after day and sleeping on the ground doesn’t bother him, Neither does eating rehydrated and jerky. What does manage to keep him from backpacking for more than a week at a time, is pooping in a cat hole.

But there have been some incredibly memorable backpack trips where he’s joined me and put up with the, shall we say, inconveniences – the Vilcabamba in Peru, a week in the San Juan Mountains of the Colorado Trail as well as the Kepler Track in New Zealand right after I finished the Te Araroa. I must say, Richard is a superb companion. An asthma sufferer, he’s not quite as fast or hard-core as me, but he makes up for it in an incredibly upbeat attitude. Even in rain and cold, you’ll find Richard cracking jokes or singing through the worst of it. He also has this delightful way of noticing little things, which even in a place as stunning as Patagonia, is a quality trait in any hiking companion.

What drew us to decide to hike this particular trail together on the other side of the globe was a picture in Backpacker Magazine. It was one of those cliché moments where I turned the page, my eyes locked onto one of the most fanciful and bizarre mountain ranges I had ever seen and I blurted out, “We should go there!”

‘There’ would be Torres del Paine National Park in Southern Chile. Torres refers to the three immense and distinctive granite towers – Torres d’Agostini, Torres Central and Torres Monzino. Paine (PIE-nay) means ‘blue’ in the native Tehuelche language and I am not quite certain if it refers to the towers themselves or what they tower over – unimaginably deep blue water.

But it was not the Torres themselves that caught my attention at first glance, rather it was the Cuernos – or horns –del Paine, spectacular spiky and multicolored magma-intruded peaks that tower some 6,000 feet above the Patagonian Steppes. Appearing as if whipped into a froth by giants, it’s tight group exemplifying a feeling of all things being extreme in this part of the world – the wind, the rain, the snow, the ice – and their power to shape everything in their path.

The Paine Range fosters unique flora habitat called the Magellanic subpolar forests. These temperate forests are filled with broadleaf trees like southern lenga beech which thrive in the cold rain forest and are sculpted into Bonsai shapes known as “flag trees” by nearly constant wind. As well, tiny Antarctic mosses and cushion plants abound alongside shrubby evergreens.

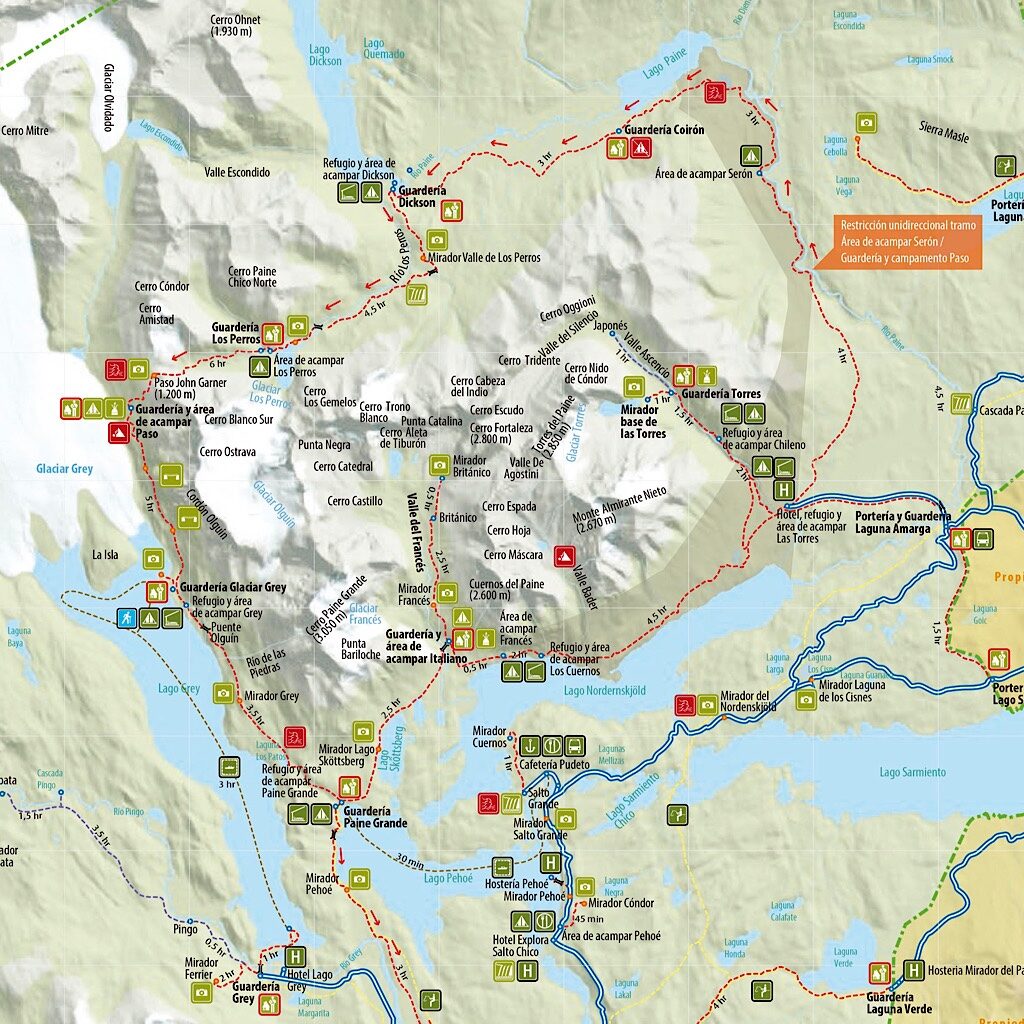

But the best part for me about this wild place, is that one can walk through it. If a tourist only has a few days, she could see most of the highlights of the park walking what’s called the “W” circuit. It moves south along the base of the mountains and up three side-trails in, you guessed it, a W. But if she has a bit more time and wants to get close to the Torres’ beating heart, she should choose to circumnavigate the entire park on the famous “O” circuit.

The “O” circuit is a counter-clockwise roundtrip that offers superb viewpoints of these bizarre mountains, as well as turquoise lakes, waterfalls that you can drink directly out of, and an enormous glacier. Situated at the highest point of the circuit, Grey Glacier is four miles wide and 100 feet thick. Walking in the park does not require a guide, although it does require some planning as far as travel by plane, bus, shuttle and boat, plus reservations for each campsite.

“We take no responsibility…”

The plan was to fly from Minneapolis to Punta Arenas, Chile via Dallas and Santiago, stay the night, then catch a bus north to the park. But these international trips have a way of not going according to plan. At our first stop, we were shuttled off the aircraft and straight to a hotel. Some vague explanation of “mechanical trouble” was all the information we received.

The hotel was fine and, by morning, we were fresh and ready to roll. A long flight south can be exhausting, but with a negligible time change, we were jazzed for the final leg of the trip. As we waited to board in Santiago, a crew member handed me a slip of paper that stated, “American Airlines takes no responsibility once you leave the aircraft in Punta Arenas.”

What now?

No one would give us a straight answer, but we soon figured out from others passengers in line that a strike had closed the airport in Punta Arenas. Not only that, the strikers had shut down the streets including any transportation to or from the city center. Things were getting violent too, with one person already killed. Eeeek! No wonder AA had no intention of taking charge. They were only flying now to act as a kind of shuttle, ferrying passengers who were trapped in the airport, an airport that was fast emptying of food and filling up with human waste.

There was no way we were getting on that plane. Luckily AA put us up in yet another hotel. I fell asleep kicking myself for not buying travel insurance and by morning, I was totally deflated.

Enter stage left, Richard to the rescue.

“I have good news and I have bad news.”

“Bad first please!”

“The strike hasn’t ended. But the good news – breakfast is by the swimming pool!”

Thus began four unexpected days in Santiago, a gorgeous city at the foot of the snow-capped Andes with a Mediterranean climate, so welcome to us Minnesotans in mid-January. We packed all the wrong clothes and I wore the same zip-off hike pants and T-shirt every day as we walked around the city, visited a winery and took a tour bus into Argentina to see Aconcagua, the largest mountain in the Western Hemisphere.

It was on the return trip down steep switchbacks that our driver told us he’d heard on the news that the strike had ended. After we returned to town, I commandeered a phone and spent the better part of the evening trying to talk the the airlines into finding us seats on the next flight. When Richard returned from the bodega with wine and cheese for a late night snack, I told him,”I have good news and I have bad news.”

“Good first!”

“We’ve got two seats on a flight to Punta Arenas! The bad news, we need to leave here at 3:00 am.”

50° south

The plane was packed, but the view was stunning of intricate fjords and glaciated mountains. Punta Arenas is a scrappy port city on the Magellan Strait filled with colorful buildings and mansions that reveal a gloried past. Sadly, with the delay, we had little time to explore before hopping on a bus to Puerto Natales, the gateway city to the Torres.

We stayed at the funky Erratic Rock Hostel, a super place to set up base, especially if you need help making plans, reserving campsites or renting gear. They also lead trips themselves and can answer just about any question you might come up with. A half-dozen others were also hiking the “O” circuit and we had fun spreading out our gear in the main room, double and triple checking we had all we needed.

The most important bot of gear? Rain gear.

The Torres del Paine receives around 30 inches of rain each year, usually in fast-moving squalls and mostly in January, the middle of South American summer. The shoulder season is often calm with crystal clear skies, but it’s much colder with shorter days. The temperatures average around 55 degrees Fahrenheit, dropping just above freezing at night. What the park is famous for, is wind. Located at 50° South, Patagonia is vulnerable to extreme westerlies, and with no obstruction from land, they can reach up to 110 mph, enough to launch a hiker and her backpack and sometimes, closing the trail.

One of the benefits of the wild wind was it would only take a matter of minutes to dry our soaking wet tent – and ourselves – after a heavy shower. But wind has its negative effects too. In 2005, a Czech backpacker was camping illegally and overturned his stove, sparking a forest fire. Fueled by the fierce winds, that accident destroyed nearly 30,000 acres and took weeks to put out. The backpacker got off on a small fine, but was later sued, and the Czech government donated money and boots on the ground to restore the fragile environment.

We never saw a trace of the damage, but realized there’s usually a reason for rules about where to camp and where not to camp. All campsites (and hostels) need to be reserved. Some are free and some cost, and, for an added wrinkle, they’re handled by three different companies. It’s a bit of a pain, but if you can be flexible with timing – and schedule well in advance – you usually can nab the sites you want. Another wrinkle is that the “O” circuit can only be walked counter-clockwise, so adjusting your planned stops has its limits.

Fortunately, we booked ahead, planning a start at Paine Grande accessed by catamaran across Lake Pehoé. Our bus ride was beautiful on the endless grasslands inhabited by guanaco, a wild camel-like creature related to the llama. We passed sheep farms and gauchos on horseback leading hundreds of them across the road as snow-capped towers above azure lakes came into view.

The entry fee is 21,000 CLP, about $31, and needs to be paid in cash. Hikers also need to register at the administration office before setting off. There, they will check that all your campsites are reserved and paid for. We did not need to take a shuttle to the dock as our bus dropped us directly, but shuttles are cheap, about $4. The catamaran runs five times a day and costs about $40 roundtrip.

We had just enough time to snap a few pictures and breath in the fresh air before throwing our packs atop an already enormous pack-pile and boarding the catamaran. The wind was up, but the skies were clear and we braved the deck to take pictures of the Cuernos, a spectacularly fanciful backdrop for the start of our journey.

Torres del Paine “O” circuit trek

- Starting Point: Paine Grande (across Lake Pehoé)

- Distance: 76 miles

- Days to Complete: 7-9 days

- Best Time to Hike: December-March

- Typical Weather: High wind, rain

- Park Fee: 21,000 CLP/$31 US (cash only)

- Permit: Proof of camping reservations required

- Huts/Cabins/Hotels: Yes

- Resupply Options: varies

- Difficulty: Strenuous

Day One, Paine Grande to Camp Italiano – 5.1 miles

It’s an easy walk from the dock to the first campsite, one that’s free and nestled in deep forest. First, we walk through thick Notro, a red-flowering shrub that lays thick along the lake. A sign reading info meteorologia makes use of the universal language of childlike puffy clouds and little suns peaking out – some smiling, some frowning. But the temps look decent and the wind speeds manageable.

The trail is wide and flat. Prickly heath berries crowd in and scratch my shins. As we round the lake, the color changes from aqua to gray matching the gloomy skies and thick fog swirling around the peaks. Beech trees stretch their arms gracefully to the side like dancers as the first raindrops of the hike hit my hat.

It’s funny how that first bit of rain can lower the spirits. It was so hard getting here with all the hassles of delays and travel changes, but here we are and I can’t see anything but my feet. What was I thinking, that somehow clear skies on the boat ride would guarantee clear skies on trail?

We throw up our hoods and push through the short downpour which stops suddenly just as we reach a wooden swing bridge over a raging river. “Only Two People At A Time On Bridge!” it reads in English, figuring most people will follow the rules if they can read them. The campsite is ahead, already packed with tents set close together amidst trees. A long, blue pipe snakes along the ground, carrying water from the river to a spigot.

Italiano is a free site with very basic amenities, a covered baño and flat tent sites. We’re glad we thought to put our toilet paper in a water-proof bag after watching one gal unravel a soggy pile of white goo to use on her visit to the cramped toilet. Most of us are cold, wet and quiet, diving into our tents early.

Needless to say, from that day onward, Richard and I wear our rain pants full-time.

Day Two, Mirador Britanico – 7 miles

We leave our tent in place and use the day to explore the first magnificent lookout on the front side of the trek – the middle bit of the “W” circuit.

But before that story, I’ll pause here to tell you a bit about our tent.

Richard is 6’4″ and doesn’t fit comfortably into many lightweight backpacking tents. We found the MSR single-wall “Skinny Two” on sale and, like Goldilocks, it was just right. It’s non-freestanding, so requires six guylines and stakes plus two hoop-like poles to keep it upright. And once set, it looks just like a Chuck Wagon. All we need are wheels…

Its best features by far are two giant windows on each side. When the weather’s decent, you can lay down and look straight out through your toes to the view. Single-wall means moisture build-up, but we never had a problem of damp gear. At four pounds, it was perfect for the conditions and remains our favorite tent for short trips.

Aside from the goofy Chuck Wagon tent, you might notice a few other funny choices, like a bandana around my hat which came without a chin strap. We also thought to wrap our closed-cell foam mattresses in plastic trash bags to keep them dry. That’s totally unnecessary since foam doesn’t absorb moisture and only needs a snap to wick any drops clinging to the outside. We both used sleeping bags warm enough for a polar expedition – bulky, heavy and not necessary since the temperatures never dropped below freezing. But they were cozy.

Before we leave for the mirador or lookout, we pack food for the day and take water bottles to gather water directly from the many streams we’ll cross and drink its delicious coolness without filtering. It’s steep, rocky and muddy and no one joins us through the thick beech forest. Our soundtrack is booming and cracking of ice slabs breaking free from colossal Frances Glacier. We’re pleased we use trekking poles, ones we bought recently after backpacking a few days on the steep, slippery rock of Minnesota’s Superior Hiking Trail. While those mountains have nothing on these, descending I could barely find footing and realized I needed “extendo-arms” to balance. The Torres is ten times as awkward, even with a day pack.

Up and up we go coming to large boulders that serve as seats. Here we pull out a Sahne-Nuss chocolate bar. My boss at the time, Daniel, was raised in Chile and made us promise we’d pick up a bar for him. Of course we had to test our own and added several to the food bag.

It’s a day of views, clowning around, chocolate for lunch and taking all the time we want to fall in love with the environment, one we have completely to ourselves. The return challenges the knees, but rain never comes even under threatening skies.

Day Three, Camp Italiano to Camp Chileno – 11.4 miles

The day opens overcast, but dry. We pack up for a long but mostly flat hike along gorgeous Lake Nordenskjöld the imposing Mount Almirante Nieto above most of the walk. Our packs are getting lighter and we’re finding a rhythm, though quietly hoping for a clear day sometime on this hike.

The island-dotted lake comes into view below, still a chalky blue beneath glacial moraine and a snowy range beyond. The trail weaves between impressive boulders that appear they’re only pausing before continuing their downhill slide. From here, the Cuernos begin to recede, their multicolored striations jutting into mist. Around 13 million years ago, a pod of granite known as laccolith heated up adjacent mudstone and sandstone and converted it into a dark brown crown, something called a “metamorphic contact aureole.”

Because all of this lies at nearly 10,000 feet above sea level, the altitude and latitude was ideal to feed glaciers during the Pleistocene, ones that stripped away the metamorphic rock, leaving just a few scraps in fanciful shapes. For obvious reasons, geologists consider the Cuernos del Paine one of the greatest examples of this process in the world and truly, one of the most magnificent.

But soon, they disappear and we work our way to the rocky shoreline. I snap a picture of Richard just as squalls tornado across the lake. He ducks his head and walks on, awaiting a pelting that lifts small stones straight into the air. The rain passes and we walk comfortably without jackets. At Refugio Las Torres, we take a pause to sit on actual benches. We’re pleased we can hike this without a guide and are self-sufficient, but it’s nice to know food and shelter is available – for a fee.

The going is steep up the aptly named Valle Ascencio, mostly eroding rock populated by beech trees with wide limbs. The wind is less in this V, but the river below crashes loudly as we work our way to another forested site. A sturdy wooden bridge leads, a much better method of crossing than the previous on large boulders.

It’s early to bed because tomorrow we’ll wake up early enough to watch the sunrise on the Torres themselves.

Day Four, Mirador base de las Torres and Japonesé – 9.5 miles

A symphony of alarm clocks, all slightly off-pitch, wake us up in pitch dark. The wind is light in this thick forest as we join our early rising neighbors. We share the same goal – to reach the viewpoint at the base of the Towers before the sun comes up. It’s a picture-postcard view and perhaps the whole point of coming here in the first place.

I’m an early riser and one who easily gets going in the morning. It certainly helps that we plan to leave our tent in place so we can use the whole day to explore. But I’m surprised to see we’re the last to leave, slowly following the arc of our headlamps up an arduous path.

Richard goes into low-gear, staying “under his breath.” That’s an expression I heard from a climbing guide who attempted to describe how one reserves their energy on long approaches at high altitude. The idea is to never move so fast you breathe fast. Sure, things might feel heavy and labored, but it helps you find a good pace, one you can keep going over a long period of time.

It takes a few hours to get to the lookout, barely lit in a dull gray. It’s packed up here and everyone is shivering. So coming behind them with less time to wait turns out to be a plus. We have just enough time to find a spot in the boulder field to sit, set up the tripod and have breakfast as the show begins.

Pink and purple mist opens and closes the view on the spiky towers, the water an opaque turquoise under precipitous cliffs and sharply angled scree piles. Sun filters in from behind, glowing on the blocky rock. A few drops hit us and transforms the spotlight into a rainbow. Soon, everything lights up and the crowd breaks into applause.

As they scatter back to camp, we linger, climbing down the rock pile toward the glacial lake. Mist obscures, then opens up again as the wind picks up. We’re standing on a flat rock watching the towers reappear as the lake rises an inch to lap at our boots.

That’s the cue to take our leave. We walk back to the main trail heading down to the campsite or further up the valley. We decide to take it, up and around the Torres towards the Valle del Silencio. The path is rockier with numerous river crossings, cushion plants and Antarctic roses cling tightly. Bright yellow Magellan barberry tucks into every crevasse available. After one wide river crossed on a downed log, we enter a meadow perfect to flop our bodies for a respite in a bed of soft grasses.

The trail gets rockier as we continue the ascent, less a trail and more a careful sidle along a scree pile. The sky clears as the wind picks up. Every time we lift a foot, we feel an uneasiness and instability. At one spot, the entire trail is wiped out by a landslip. We’re forced to climb in and up it to regain the already thin path along loose rock that makes a musical “plunk” with each footfall. The towers loom into view just as we level off and begin heading down the other side, but the wind is howling through the channel.

I really want that view, but it doesn’t feel prudent. Getting this far all on our own is enough this time. We sit on the rocks as the wind buffets us. It’s not cold, but threatening and we don’t dare open our packs for a snack in this exposed place.

Down we go, over the landslip, across rushing streams and past bright green alpine plants carpeting rock on the warmer side. “Chuck Wagon” is still in place and a welcome site in the beech forest. Dinner is made in a shelter protected from the wind. So many stupendous views and all that rarefied alpine air has us knocked out in no time.

Day Five, Camp Chileno to Camp Serón – 11.3 miles

We wake to a glowing sunrise on the towers peaking out above the forest. The sky is crystal clear at last and it’s time to push onward beyond the “W” and onto the “O.” Here, the land changes dramatically and the crowds thin. The trail rises above a rolling landscape reaching out towards wide rivers, mountain ranges in the distance. We can still see the towers jutting above the humpy moraine, but things are different here, more like the wild west.

I pass a man on a dusty rise and say, “Hola!” He turns to talk to me showing his specially-made T-shirt to mark this occasion. “80 Años,” it reads. “Rafael, Torres del Paine, 2011.” What a feat celebrating his 80th birthday by walking the same trail I’m walking in my mid-40s. It appears his supplies are being carried by horses, but still, it’s quite impressive.

We cross Rio Paine on a swing bridge and head into open fields filled with daisies just as the rain returns. I throw myself in them anyway, not caring about getting wet anymore. A karakara hawk with an impressive violet bill and a brown beret walks closer looking for handouts.

We cross a stile and a twisted wooden bridge then arrive in bright sunshine at Camp Serón, a beautifully appointed site with hot showers, bathrooms, a small store and even equipment rentals. I guess now would be the best time to change out a few things before heading to the highest point at John Garner Pass.

We’re all set and famished, so grab a picnic table next to a friendly Chilean. Rodrigo is close to our age and carrying far too much gear. Still, he’s so proud of that gear, all tuff he bought when an exchange student in the United States. Rodrigo and Richard fall into conversation quickly as I cook up a dehydrated Indian dish. In no time, we knock out to crickets and the whistling trill of an austral pygmy owl, the air still and warm in this field.

Day Five, Camp Serón to Camp Dickson – 11.5 miles

The day begins clear and still, the mountains shimmering above fields of humpy mata barossa. It’s a steady climb over a small pass with views down to the bright aqua Lago Paine. A horse train passes us led by a guacho straigt out of central casting decked out in checked shirt, kerchief and beret.

It’s easy walking on an easy day and the entire camp falls into a familiar comfort, the older people including us, Rodrigo and his girlfriend, and the younger, mostly early 20-ish Chileans in groups of three using this hike as their rite-of-passage between college and adult life.

I hear them laughing as they pass and Rodrigo tells us later they’ve called us the “oldies” in a kind of Chilean slang. It’s not meant to be hurtful, just an observation that we may walk more carefully and slowly, but we all end up in the exact same place each night. Funny thing about Chilean Spanish – I can’t understand a single word. They speak in a fast, clipped accent that sounds more Italian than Spanish and pepper their sentences with handfuls of slang. I give up trying to talk to them and accept the reality that they’ll keep making fun of me behind my back.

Here we walk past giant Lenga, beech particular to the temperate southern Andes. They can grow to a height of 100 feet but compensate by producing tiny ridged leaves that fill the trail like snow. Olive green moss climbs up one side and trunks denuded of their bark live on in twisted gray ghosts, their arms seeming to beseech the sky.

Camp Dickinson is perfectly situated on a small peninsula jutting into the lake. It sports a dorm, a restaurant and bar and a small store also offering rentals. We face Chuck Wagon so the picture window looks directly gat laciated mountains on the opposite side turning pink in the sunset. A picnic table serves us well and we pass on libations, happy with what we brought.

Will the weather hold as we walk up into those glaciers? One can only hope.

Day Six, Camp Dickson to Camp Los Perros – 7.6 miles

We leave Dickson on a crystal clear but bitterly cold day. Fresh snow dusts the mountain peaks in a perfect reflection. It’s easy walking on the shore through thick trees and soon most everyone strips down to T-shirts. A Megellanic Woodpecker with an extraordinary crimson head flies past in a scarlet streak, clinging to a dead trunk with extra-large talons.

He drums quickly then pulls out something gooey. Hopping higher, his head swivels about to see who might be watching. Us – and…another bird! A female joins him, entirely black with white flight feathers tucked deeply into her body. Only the base of her bill is red. What a treat! They’re the largest woodpeckers in South America and among the largest in the world, like Woody Woodpecker come to life.

But they don’t stay long as if knowing their wonderfulness depends on the fact that they’re infrequently sighted. We head on, crossing Rio los Perros on a sturdy bridge over a narrow and deep chasm, then climb towards a glacier, calving into Los Perros Lake. Shaped like an “I,” the top is full of bright blue crevasses that seem to pour into a canyon, spreading out into a messier blob of white that breaks off into floating bits the size of small cars.

Richard decides this is an ideal place for lunch and chooses a rock with a view. I’m taken with the colorful flowers eking out an existence in this harsh environment. It’s hard to remember that we are here in the middle of summer, at the hottest time of year. Imagine how brief their growing season.

We eventually lumber on, walking on top of moraine, deep and scupted as if moved into place by bulldozers. Ahead, we see the pass. Named for a British mountaineer who created this trail in 1976, John Gardner will be the highest point of the “O” at nearly 4,000 feet. It’s said to be treacherous with high winds blasting sleet and snow at the pass followed by a muddy and eroded descent.

But that’s all for tomorrow. Right now, the Chuck Wagon is set with the window wide open to a view of high, craggy peaks and a thunderous waterfall still loud at a distance. As I set the sleeping bags, it all looks so cozy, I crawl in for a wee nap. Dinner is far off and there’s nothing to do but rest.

Richard wakes me up. “I have good news and I have good news.”

“Oh, hi. How long did I sleep?”

Richard tells me only about twenty minutes and proceeds to share “the news” – another Sahne-Nuss for me and a beer for him. Soon, we join everyone in the kitchen, a wooden structure with green tarp walls. All our friends have arrived including the young ones and old ones, including Rodrigo. He’s having serious trouble with his stove and can’t get it to light. It’s in pieces now on full displayand his hands are black from soot.

Richard sits next to him and offers a hand. The chocolate wasn’t enough for me, so I focus on making our dinner. It does seem like they figured things out because the stove eventually is put back together and a pot is simmering.

¡Buen provecho!

Day Seven,Camp Los Perros to Camp Grey – 10.3 miles

The big day arrives when we’ll hike over the John Gardner Pass. At close to 4,000 feet, it’s the highest point on the “O” circuit. At the mess tent last night, and English couple – and part of the “oldies” – started up with the fear-mongering.

The winds can be so fierce at the top, you’ll need to crawl!

And the mud on the descent is thick and slippery and completely eroded, so you’ll likely need to crawl down as well!

Most of the people here at camp have NO BUSINESS walking over the pass!

Needless-to-say, they were not helping.

We’re up at dawn and put rain gear on over all our clothes. We check and double-check we have water and snacks and the right attitude. Just as we throw on our packs, the English couple saunters by giving us a once-over. I smile and tell them to have fun even though I feel them judging us.

They move fast and soon disappear up the steep mountainside. It’s a rain forest most of the way filled with delicate orchids and slipper plants, like the bright yellow capachito. The mud begins almost immediately, with thick roots to negotiate, often just as wet and perilous. Some kind souls have placed wooden boards, but these are slowly getting sucked deeper into the mire.

Up and up we go, the sky heavy and gray with mist hanging low on the mountains above. Two of the young kids with heavy packs march past, giving us an “Hola,” in raspy voices. Richard leads us onto a plateau of moss and cushion plants, glorious sprays of flowers in pinks, purples and whites gaily reaching to the sky. We cross one rushing stream after another before hitting the bare rock. Next to us is the tongue of a glacier moving down the valley.

Orange poles, just like in New Zealand, guide the way, but the path is obvious in rocky rubble and more a steep ramp than anything technical. Suddenly I realize something – only light mist hits us from above and the various mini-waterfalls are all I hear besides my heavy breathing in what is mostly silence. There’s no wind! But will that remain so as we crest the top?

I look back to the lake far below, still visible all this way until fog mushrooms and obscures everything. We’re almost to the top of the world, it would seem. Ahead is one more pole, but this one is covered in cloth – hairbands and odd socks, rubber bands and bits of string. This is it!

The rock changes color from silver to bronze as mountain peaks come into view. Snow covered and jagged, they’re swimming in a sprawling ice-field as if in the ocean. Grey Glacier squeezes between mountain peaks, filling every low area, its fingers reaching into every valleys. What’s un-ocean-like is that the glacier’s tipped downward, sloping towards a lake out of view.

We marvel at its size and snap picture after picture, unable to capture the overwhelming beauty of this monstrous glacier. As we hang out on top, stunned and amazed, we realize the wind is not here either and crawling won’t be required. We are incredibly lucky. The English couple is long gone, but they were right, the wind can be vicious. So much so, that the rangers at Los Perros will close the trail if they deem it too dangerous.

The sky is not clear, but the clouds are high and offer dramatic lighting, magnifying its grandeur. We walk quickly down the other side on a similar rocky ramp directly feeling its cold power, as if it were a living being next to our insignificant selves.

Our step is sure and our mood light as we move towards the lenga beech forest below, the textured crevasses coming into focus. One deep pit is in a bright ultramarine as if someone were making a slushy for Paul Bunyan. As we enter the forest, our joy and elation are crushed. A slog awaits of washed out path and mud. The park placed pipes as handrails, but they’re slippery and bent. It’s tough-going, but beautiful forest, a fairyland of bright yellow daisies and moss-covered rocks. Every so often, a notch opens to the glacier, closer now and jagged. We come out to the edge of the mountainside, and begin sidling steeply as the lake comes into view ahead filled with floating ice.

Easy walking ends abruptly again as the mountain crumbles away into deep canyons of eroded rock and debris. This must have been a past glacial trail. Now, water tears it away stone by stone. The park placed ladders here since it’s far too steep and crumbly to climb. “1 a la vez!” it reads and we carefully climb up and down one at a time, hanging tightly to the slippery metal.

In one canyon, I notice a rope between the ladders and realize it’s used tp cross the stream in flood. Thankfully, we can just wade across and jump from stone to stone. It’s up and down, then out on the edge and back into a deep ravine before we’re spit out at the head of the Lago.

It’s not far now to the campsite, again set deeply in the woods and safe from the wind. Like Italiano, things are pretty basic with only outdoor bańos and water. We return to the mirador and watch the mountains turn pink and the ice turquoise, then cuddle in close for a chilly sleep.

Day Eight, Camp Grey to shelter south of boat terminal, 12.9 miles

The final hiking day is easy, so we return down the short trail to the mirador, the furthest west of the “W” trail and a spectacular look out towards the glacier. Boats are already on the lake taking visitors directly under the calving glacier. We’re up high and the wind is up. Threatening gray clouds hang low within touching distance.

We play on the edge taking pictures as the wind (from behind fortunately) buffets us. What would it have been like coming down yesterday in this wind, we both wonder silently. It makes no difference because we’re here and its clear enough to see the spectacular glacier oozing out of the valley. Grey is the biggest glacier in a park filled with glaciers and part of a larger ice mass called the South Patagonian Ice Field spanning 4,700 miles.

The trail will return us to the dock where we’ll catch the catamaran back to our bus. Mostly, we’ll walk along huge Lago Grey as the glacier recedes and we come around again to view the spectacular Cuernos del Paine, like old friends. We walk quickly and not one raindrop hits us from the overcast sky.

From windswept and gunmetal Grey Lake we cross the humpy, mata barossa-covered moraine towards Lake Pehoé, placid in an opaque aqua. The horns come into view, as well as hundreds of tents. The English couple is here already set up and smug. A few of the kids wave and we see Rodrigo further in.

It doesn’t look like such an appealing way to end this epic. And that’s when I remember something I was told back at the Erratic Hostel in Puerto Natalas. It’s a bit of advice I tucked away because I didn’t have the context for the information yet. It was to skip this campsite and walk a bit further south to a shelter. There’s nothing much to see there, but it’s usually empty and has the most “soulful” nights, if I remember his words correctly. Richard has the same vibe of feeling crowded and let down by such a mass of people and is eager to move on.

The trail takes us further along the lake, the range of mountains appearing bigger now from this perspective. Just as we reach the end of the moraine and the trail ducks down into a valley, the sun peaks out and lights up the humpy green hills below the striking peaks as if tipping its hat.

It’s not far on easy trail to a small clearing of land, just as advertised with a large three-side shelter and an outhouse. We set up near thick bushes out of the wind then spread the last of our food out to cook. No one shows up in this quiet and lonely place and we dawdle out of the wind, staying up until the last of the light disappears around 11:00 pm.

When we retreat to the tent, the wind dies and the stars come out. It’s the first time on the trip we can really see the night sky, the kite of the Southern Cross blazing bright above our heads in the milkiest of milky ways. We lay close on the grass and stare at our sky, happy we decided to add a few more miles to the circuit and wander down to this out-of-the-way spot.

Homeward bound

It’s a gray morning with big winds as we walk back through the grasslands and over the humpy moraine, the horns coming back into view. We say goodbye to giant beeches, protected long enough in this valley to grow tall and thick. We say goodbye to the wildflowers, fierce and bright in this harsh environment. We say goodbye to shockingly blue water and mountains, so grand they look formed by a master sculpture. We say goodbye to the wind and rain, the hawk and the owl, rock and ice. We’re grateful for our luck having reasonably decent weather, strong bodies and the persistence to get ourselves here even when the trip looked like it was doomed.

The return trip on the catamaran is just as lovely, though most people stay below out of the wind, taking a nap or planning their next adventure. Our bus driver careens down the gravel road, honking at the guanaco as he keeps his speed on sharp curves. The day ends with local brew and local fare followed by a restful night dreaming of the long trip home, which, shockingly, doesn’t have one hitch the entire way.

4 Responses

I didn’t get this post, as I have for your past trips, but a friend forwarded it. Please add me to the list because I have thoroughly loved reading about your nail biting past blow by blow hikes.

thanks Susan! I will. More nail biting to come 🐥

Totally enjoyed reading this trip journal. I’m amazed Alison how you know all the names of all the plants, critters and birds! The pictures were great. Thanks for sharing this blissful hike for us armchair travelers.

thank you so much Merry-Ann! It was a trip-of-lifetime and before Blissful and blogging, so I had to go back and piece it all together. Such an extraordinary place. I am particularly fascinated that the beech are also in New Zealand because of common ancestors in the Pleistocene! Kia kaha, friend.